What if your most sensitive data became accessible in an instant?

The growing excitement about the advent of quantum computers is justified for a subject that is no longer science fiction but involves a new kind of threat.

Indeed, according to the predictions of numerous experts such as the Global Risk Institute, quantum computers should soon be capable of solving the mathematical problems underlying current cryptographic standards – which would consequently render obsolete the traditional systems protecting our communications, our finances and our critical infrastructures.

For businesses, the urgent question is no longer whether this threat will become a reality, but when. How can we anticipate the operational and structural impact of this technological upheaval, while at the same time responding to the growing number of regulatory recommendations on the subject? What tools should be adopted to guarantee the confidentiality and integrity of data in the near future? It’s a major challenge, but solutions are being studied, such as post-quantum cryptography (PQC), which is already being widely adopted by the international community.

The quantum threat

Today, the security of information systems relies mainly on symmetric and asymmetric (or public key) cryptography and hash functions. These categories are represented by algorithms that are widely used today, in particular AES, RSA, ECC and SHA for hash functions. Massively adopted by the global community and natively integrated into many modern devices, these algorithms have proved their worth for decades in ensuring the confidentiality, authenticity and integrity of data exchanges.

The mathematical problems on which these standards are based are sufficiently complex to ensure that even today’s best supercomputers have no brute-force capability.

The quantum computer is reshuffling the deck.

These machines are based on physical principles that are fundamentally different from today’s classical computers. Thanks to the phenomena of superposition and entanglement, a quantum processor can process different physical states simultaneously. What is often described as ‘quantum parallelism’ does not correspond to simple classical parallel computing (where several cores execute identical tasks), but to the ability to explore multiple execution paths simultaneously. For some algorithms, this approach can considerably reduce the search space and speed up processing.

A key question then arises: are there already algorithms capable of exploiting these quantum properties, and thus of overcoming current encryption standards?

In 1994, P. Shor, followed by L. Grover in 1996, introduced algorithms incorporating quantum computation processes to solve certain complex mathematical problems. The first allowed large numbers to be factored exponentially faster than a conventional algorithm, while the second optimised the search for an element in unordered sets. Until now, the characteristics of classical computers have made these algorithms impractical, but the emergence of quantum computers will radically change the situation, making them usable.

Indeed, the best supercomputer would take 1.02 x 10¹⁸ years (one trillion years) to break AES-128 by brute force and 10¹⁰ years (10 billion years) for RSA-2048 using today’s best methods. By comparison, a quantum computer running Grover’s algorithm could break AES-128 in 600 years, while Shor’s algorithm would overcome RSA-2048 in just 8 hours with a machine of 20 million qubits.

Faced with this threat, AES and symmetric cryptography, as well as SHA-256 and hash functions, remain viable by doubling the size of the keys used, but asymmetric cryptography needs to be rethought. With this in mind, post-quantum cryptography is emerging as the most promising solution.

What is post-quantum cryptography?

According to the ANSSI, ‘post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is a set of classical cryptographic algorithms including key establishment and digital signatures, which provide conjectured security against the quantum threat in addition to their classical security’.

This therefore refers to all the new asymmetric encryption algorithms capable of guaranteeing security against both traditional attacks and the new quantum attacks. The difference with those we use today lies essentially in the mathematical problems underlying the algorithms, chosen to remain complex to solve, even for a quantum computer.

Why is this solution considered the most promising?

PQC is not the only response being considered to the quantum threat, but it is widely regarded as the most viable solution by the international community. Several factors explain this interest, including

– Continuity with current systems, facilitating its adoption and gradual integration into conventional infrastructures.

– Advanced maturity, with standards already established and supported by the main cybersecurity authorities.

Continuity with current systems

How does this classical type of cryptography protect encrypted data against quantum attacks?

PQC does not imply a paradigm shift in our approach to securing infrastructures. As mentioned earlier, PQC is part of the family of asymmetric cryptography and therefore retains the same operation and objective as current public key algorithms. Its resistance to quantum attacks is ensured by the nature of the underlying mathematical problems, which are different from those used in conventional asymmetric cryptography. This structural difference also means that cryptography can be integrated more seamlessly into today’s digital infrastructures, ensuring a gradual transition to a future in which PQC completely and effectively supplants modern encryption standards.

Advanced maturity

The second major advantage of the PQC is its maturity compared with the other options considered. This year saw the publication of PQC standards by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in August 2024.

This process began in 2017 with 69 initial candidates, 4 of whom were selected to become the new PQC standards. None of the other solutions put forward to counter the coming threat, including quantum cryptography (based on the use of quantum properties as opposed to PQC, which can be implemented on conventional computers), have been the subject of a standardisation process.

Furthermore, national cybersecurity bodies such as ANSSI (France), BSI (Germany), NLNCSA (Netherlands), SFA (Sweden), NCSC (UK), NSA (USA), etc. all agree that CQP is the best way to protect against the quantum threat, and that the priority for businesses should be to migrate to CQP systems.

When and how can this technology be implemented?

The predictions of research bodies on the advent of the quantum threat are still fairly disparate, but all agree that quantum computers capable of executing the algorithms responsible for the future obsolescence of current cryptographic standards, known as Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer (CRQC), will render RSA-2048 obsolete, in particular, within the next 15 years. It is difficult to predict exactly when the quantum computer will be ready and will achieve sufficient performance for concrete use cases but cross-referencing the recommendations of organisations such as the NSA with the predictions of experts on the subject means that we can estimate the emergence of the first CRQCs between 2033 and 2037.

Harvest now, decrypt later

However, we do not have 10 years to arm ourselves against this threat. Data in transit today remains exposed to ‘harvest now, decrypt later’ attacks. These are attacks based on the interception and long-term storage of encrypted data, pending technological breakthroughs in decryption that will make it readable in the future.

The data targeted by this type of attack is mainly data in transit, as it is during transport that protocols such as TLS use asymmetric key pairs. It is at this point that the data is ‘quantum vulnerable’ and therefore interesting to intercept and store to decrypt it later. Data at rest, on the other hand, is generally encrypted using symmetrical algorithms, and requires to be exfiltrated to be captured, so it is not the target of these attacks.

The main risk of these attacks remains the violation of long-term data confidentiality. Depending on the sector, particularly financial or industrial, data can remain sensitive for long periods, so access to this information can have multiple serious consequences. It is reasonable to assume that attackers could currently recover a considerable quantity of encrypted data to decrypt it later. It is therefore imperative to start migrating to cryptographic systems that are resistant to quantum algorithms today.

Recommendations from organisations on preparation

CISA, the NSA and the American NIST, to name but a few, are urging companies to get ready now by drawing up a quantum roadmap, led by a dedicated project team, whose aim would be to plan and supervise the organisation’s migration to PQC.

The project framework will need to focus on 3 main areas:

- Cryptographic inventory: the aim is to understand the organisation’s exposure to vulnerable cryptographic mechanisms. This involves identifying the technologies used in systems, network protocols, applications and programming libraries.

- Risk analysis: this aims to prioritise the assets and processes to be secured first. The aim is to assess the criticality of the data being protected, and also to anticipate the length of time it will need to be protected. This analysis is based on the cryptographic inventory carried out upstream and enables efforts to be targeted where the impact of a quantum attack would be most critical.

- Supplier responsibility: the transition to post-quantum cryptography also involves working closely with technology partners. Companies need to ensure that the solutions they use are crypto-agile: can current products be upgraded to systems that are resistant to the quantum threat, or will they need to be replaced to avoid obsolescence?

The migration strategy we recommend at Wavestone takes the main steps outlined by CISA, NSA and NIST, and adapts them to the operational realities of each company:

- Strategic phase:

- Understanding and raising awareness: Firstly, this involves training and informing all those involved (management, business teams, technical teams) about the impact of the quantum threat, the issues involved in post-quantum cryptography, and the main regulatory guidelines.

- Risk assessment and initial inventory: Mapping of cryptographic uses (protocols, libraries, applications, etc.) and identification of sensitive data that must remain confidential over a long period. It is also at this stage that the company’s maturity is assessed and the most critical projects prioritised.

- Framing the programme: On the basis of the risks identified, the overall roadmap (objectives, budget, organisation) is defined. A dedicated team – or ‘centre of excellence’ – is set up to steer the transition, coordinate the various projects and define the success indicators.

- Quick wins

- Before embarking on a more extensive transformation phase, we recommend the rapid launch of low-investment initiatives, such as including post-quantum clauses in contracts (with suppliers and partners). The aim is to obtain tangible returns, raise stakeholder awareness and create a positive momentum around the project.

- Transition programme

-

- Test of an initial use case: Selection of a representative use case to deploy the first post-quantum cryptographic algorithms or mechanisms under real conditions.

- Detailed inventory (second iteration): We then need to refine the mapping of cryptographic components (PKI, key management, network protocols, encryption libraries, etc.) in order to plan the migration precisely.

- Modernising ‘digital trust’: This involves updating infrastructures (PKI, certificate management, key rotation policies, etc.) and implementing procedures to accommodate new algorithms.

- Migration and monitoring: Progressive deployment of post-quantum algorithms on critical systems, while maintaining service continuity. This phase is accompanied by controls, performance tests and security checks. Eventually, the entire IS is covered, guaranteeing continuity and regulatory compliance.

This roadmap, which is both pragmatic and in line with the recommendations of the relevant bodies, guarantees a controlled transition to post-quantum cryptography.

Hybridization mentioned in Europe as an important step in the transition

In a joint publication with its European counterparts BSI, NLNCSA, SNCSA and SFA, ANSSI also recommends that preparations for this transition should begin as soon as possible. Although the new PQC standards, including algorithms, implementation instructions and their use, were published by the NIST in August 2024, these bodies are not encouraging the immediate integration of these algorithms into companies’ cryptographic systems. The ANSSI has even announced that it ‘does not approve any direct replacement in the short or medium term’. The reason for this is ‘a lack of cryptanalytical hindsight on several security aspects’; despite its completed standardisation process, PQC is not yet considered mature enough to guarantee security on its own:

– Several algorithms that were finalists (and therefore considered promising) in the NIST standardisation process have been the subject of classic attacks that have been successful. The SIKE algorithm was defeated in 10 minutes, and Rainbow in a weekend.

– Dimensioning, integration of algorithms into communication protocols and the design of secure implementations are other aspects on which progress needs to be made, according to the ANSSI.

Consequently, unlike NIST, ANSSI and BSI, among others, recommend that organisations adopt hybrid systems. This concept consists of ‘combining post-quantum asymmetric algorithms with well-known and well-studied pre-quantum asymmetric cryptography’ (ANSSI). In this way, we can benefit from the effectiveness of current standards against classical attacks, and from the predicted resistance of PQC against quantum attacks.

Hybridization is possible for key encapsulation mechanisms and digital signatures. Each classical operation is replaced either by:

– successive execution

– parallel execution of the 2 algorithms, pre-quantum and quantum.

The second option can be implemented to reduce the loss of system performance. These hybrid schemes also require the players involved to support both types of algorithms.

This is a scheme where ‘the additional performance cost of a hybrid scheme remains low compared with the cost of the post-quantum scheme’. ANSSI believes that ‘this is a reasonable price to pay to guarantee pre-quantum security that is at least equivalent to that provided by current standardised pre-quantum algorithms’.

On the other side of the Atlantic, we are much more nuanced than our European counterparts on this issue. Although the benefits of hybridisation are recognised by the UK and US cybersecurity authorities, the NCSC and NIST insist on the temporary nature of this solution and do not impose hybridisation as a mandatory step before migrating completely to PQC. The NSA explicitly states that it has confidence in PQC standards and does not require the use of hybridisation models in national security systems. In summary, the decision to use these models must be taken taking into account:

– technical implementation constraints

– the increased complexity (two algorithms instead of one),

– the additional cost,

– the need to transition a second time in the future to a total PQC system, which can be a complex exercise in crypto-agility – i.e. the ability to modify one’s cryptographic infrastructure rapidly and without major upheaval in response to changing threats – for some companies.

Regulatory aspects

There are currently no European regulations setting out explicit requirements for post-quantum cryptography. However, some of the various texts on data encryption (NIS2, DORA, HDS, etc.) explicitly require state-of-the-art encryption to be applied. In particular, DORA requires the constant updating of the cryptographic means used in relation to developments in cryptanalysis techniques. It is therefore possible to consider this as a first step in guiding organisations towards the concept of crypto-agility.

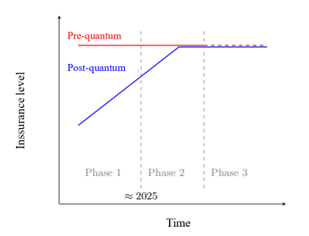

Despite the current lack of requirements, ANSSI is planning a post-quantum transition plan in 3 phases:

- Phase 1 (in progress)

Effective post-quantum security through hybridisation remains optional and is considered by the agency to be defence in depth. The security approvals issued by ANSSI remain unchanged and only guarantee pre-quantum security.

- Phase 2 (after 2025)

Quantum resistance becomes a security property. Post-quantum security criteria for PQC algorithms will have been defined by ANSSI and will be taken into account when issuing security visas.

- Phase 3 (after 2030)

It is estimated that the post-quantum security assurance level will be equivalent to the current pre-quantum level. Hybridization will therefore become optional; security visas may be issued for companies using post-quantum schemes without hybridization.

In addition, depending on the context, ANSSI may decide to grant security visas only for long-term post-quantum security.

In the USA, NIST’s post-quantum transition plan is not definitive, but the obsolescence of RSA and ECC is already projected for 2030, followed by a total implementation ban in 2035; hence the announced target – aligned with the NSA – for completion of the migration to PQC in all federal systems in the same year. Depending on the requirements of different sectors, it may be necessary to make the transition more quickly, depending on the associated levels of risk.

Although 2035 seems a long way off, the full migration to post-quantum cryptography is a long process, and the initial phases of cryptographic inventory, data classification and risk analysis, in particular, require considerable time. It is therefore essential to start today to plan for a successful transition.

The advent of quantum computers is therefore no longer a distant hypothesis, but a certainty that will redefine the foundations of cybersecurity. While the precise timing (2033-2037) remains uncertain, the regulatory pressure from cybersecurity institutions is becoming clearer, and the impact on data confidentiality and integrity is unavoidable. Every day that goes by without adaptation increases the vulnerability of companies to future attacks.

And yet, solutions already exist: post-quantum cryptography, although not yet fully mature – especially when it comes to implementation – offers a promising response to this threat. Standardised and supported by the major international bodies, it represents the first step towards sustainable security in the quantum era.

However, adopting this technology is not simply a matter of technical deployment. It is a strategic transition, an exercise in crypto-agility, and an opportunity for businesses to assert their resilience in the face of technological upheaval.

The question is no longer whether your organisation will be ready when the first quantum computer capable of breaking RSA-2048 sees the light of day. The question is whether it will have anticipated this future, by arming itself now with the tools and plans needed to turn this constraint into a competitive advantage. The future of security starts today.