The online payments market is constantly changing: to illustrate, from 2022 to 2023, the number of mobile payments has increased by 90.4%, and for e-money payments, the increase was 29.7%[1].

In order to manage this evolution, the European Union has adopted the Payment Services Directive. In its second version (PSD2), published in 2015, this directive was set to create and regulate the Open Banking sector. The goal was to enable users to provide an access to their banking and accounts data to innovative new actors such as aggregators and payment initiation providers, while ensuring security and competition at a sufficient level in the payment services ecosystem.

Unfortunately, PSD2 limits have started to show, including:

- Unharmonized legislations leading to « Forum shopping » which is a legally grey practice consisting, for a payment services provider, to choose their incorporation country based on the local legislation that would be most favourable to them.

- A gap that was not sufficiently closed between banks, which are in a privileged position to provide payment services to consumers, and third-party providers that depend on them.

- Fraud, with methods changing along with the payment markets, and for which PSD2 provision are now considered as insufficient.

Therefore, the European Union has introduced a draft for a 3rd version of the directive, the so-called PSD3, on June 28th, 2023. A final version is expected for late 2024 or early 2025. The text will be enforceable 18 months after publication, which would be somewhere around Q3 2026.

How will PSD3 be introduced?

Upon reading the draft, it is clear that where PSD2 has introduced completely new and structuring concepts like the notion of Open Banking or Strong Customer Authentication, PSD3 is aiming at updating existing concepts. As indicated on the European commission website, it is

« an evolution, not a revolution ».

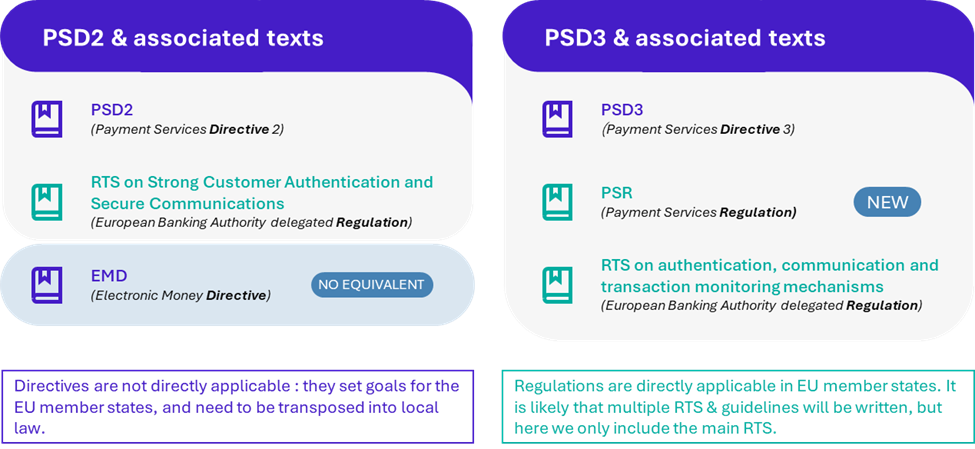

The format changes: PSD3 is introduced with a regulation called PSR (Payment Services Regulation). Its content is using a lot of elements already present in either PSD2 or its RTS (Regulatory Technical Standards). The novelty here is in the type of legislation: it is a regulation, which is directly applicable in member states, contrary to directives, which need to be translated into local law. This is one of the solutions the EU has adopted to tackle the previously mentioned harmonization issue.

The regulatory framework for e-money also finds itself simplified. The practical issues caused by the existing differentiation between online payments, regulated by PSD2, and the use of e-money, regulated by the 2009 Electronic Money Directive (EMD) will disappear since PSD3 now covers both types of services.

Additionally, PSD3 brings a few clarifications in its definitions. Though these are not technically new changes, here are some of them:

- Deposit accounts, such as savings accounts, are now explicitly excluded from the definition of payment accounts.

- Aggregators are now defined by their capacity to collect and consolidate banking information on payment accounts and the like, regardless of whom the aggregated information is destined to.

- Multifactor authentication relies on multiple factors in classically defined categories (knowledge, inherence, possession), but it is now clarified that to count as an MFA, authentication factors need not belong to different categories, they only need to be independent (defined as: compromission of one does not affect security of the other).

What will the various payment service providers have to do to comply to PSD3?

Key PSD3 evolutions are technical changes with the aim to protect consumers against fraud.

Therefore, payment services providers will have to develop and provide new services for their users. A first example is an access permissions dashboard enabling them to monitor in real time who is allowed to access their banking and payment account information. Another example is the payee’s name verification service, wherein the name of a payment recipient is compared to the receiving account holder name, and the result of that comparison is made available to the payer to try and prevent identity theft.

Likewise, PSD3 has some provisions planned for strong customer authentication accessibility. All banks will have to be able to provide an adequate strong authentication means for all their users, including people with disabilities, the elderly, people with poor technological skills or without smartphone etc.

The addition of a new actor will shift the repartition of compliance responsibilities: this actor is the Technical Services Provider. They will inherit part of the compliance and audit responsibilities, especially in the case where strong customer authentication is delegated by the bank to their third-party solution.

What will be the impact of those changes?

Through the aforementioned PSD3 changes, banks and other payment services providers are incited to share and exchange information to fight against fraud: some dispositions are already taken to be able to do so while complying with GDPR.

Especially for the payee’s name verification service, Open Banking APIs will have to be updated to allow this verification by the payer’s bank. Since this operation is quite complex, and even more so when the transfer is supposed to be instant, the associated article will enter in force 2 years after the rest of the regulation (not before Q3 2028).

Users will also see new features appear, meaning some time will be needed for them to adapt and get familiar with those features. Some level of support will have to be set up for all involved parties, including users but also customer support teams, to foster a correct understanding and adoption of these features by users.

If the final text is published before early 2025, companies from the payment sector will have until Q3 2026 to achieve compliance with PSD3 and PSR.

It is essential to start considering these changes starting today and ensure a certain level of regulatory watch to stay informed of the various texts (including RTS, guidelines) that will be published by both the European Commission and the European Banking Authority.

[1] 2023 annual report, French Observatory for the security of payment means