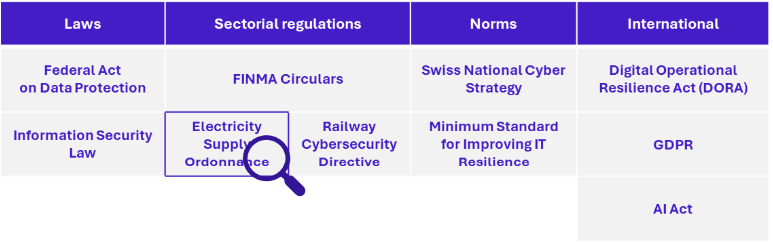

Historically, Switzerland has distinguished itself from its neighbors by adopting a less stringent approach to information system security regulations. Preference has been given to subsidiarity, a legal principle whereby the Confederation does not legislate in areas where the Cantons can. Apart from two federal laws (nLPD, LSI) and several sectoral regulations (CySec Rail Directive, Finma regulations, Directive for the security of smart metering systems data, etc.), this approach has allowed Cantons to maintain autonomy in managing cyber issues. However, the growing need for cybersecurity is leading to an increase in cyber regulations and their binding nature.

Cybersecurity Regulations in Switzerland

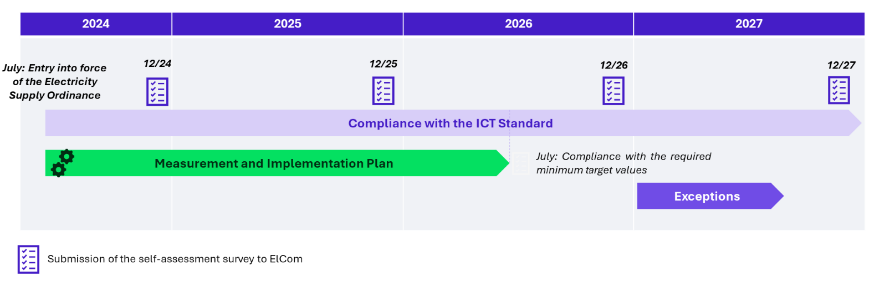

Two new binding national texts came into effect on July 1st, 2024, to establish a minimum cybersecurity threshold for the electricity supply and railway transport sectors. This article will focus particularly on the revision of the Electricity Supply Ordinance (OApEl).

Global Trend towards Cybersecurity Standardization

The cybersecurity landscape is shaped by various national and international frameworks and legislations:

- The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) of 2017 in the United States has become a standard for federal agencies to manage and reduce cybersecurity risks, following a presidential executive order indirectly mandating its use.

- In Europe, the 2016 Network and Information Systems (NIS) Directives, complemented by NIS 2 in 2023, aim to enhance the resilience of essential service operators (OSE) and strengthen the security of network and information systems.

- In France, the 2018 Military Programming Law (LPM) for the years 2019-2025 imposes obligations on operators of vital importance (OIV) to secure critical infrastructures against cyber threats.

These initiatives demonstrate a concerted global effort to bolster cybersecurity in response to increasingly sophisticated threats.

Changes for the Swiss Electricity Sector

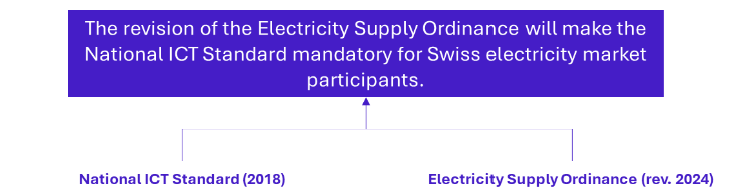

In this context, Switzerland’s minimal National ICT standard is now mandatory for the electricity supply sector.

- The National ICT Standard in Switzerland, implemented by the Federal Office for National Economic Supply (OFAE), aims to protect infrastructures against cyber risks. It covers identification, protection, detection, response, and recovery, drawing inspiration from NIST standards to assess cybersecurity maturity and provide guidance. Unlike the European NIS directives and the French LPM, this standard is not inherently binding.

- The Swiss Electricity Supply Ordinance (OApEl) specifies the Electricity Supply Act (LApEl) and regulates the electricity market to ensure supply security, with a cybersecurity component in its article 8b on data protection. Unlike the ICT standard, it is binding. Its new version, which makes the Minimum ICT Standard mandatory for electricity sector players, took effect on July 1, 2024.

Mandatory Compliance for Swiss Electricity Actors

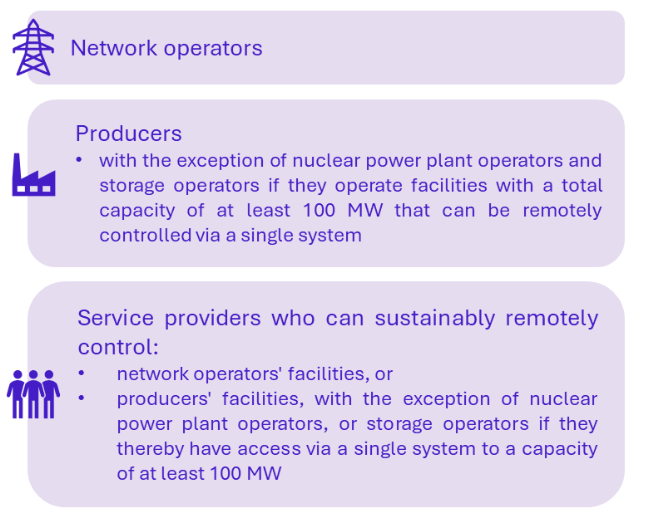

Actors that must comply with the National ICT Standard under OApEl within 24 months of its effective date :

The revised OApEl’s minimum requirements are binding upon their enactment, with no transitional period. The Federal Electricity Commission (ElCom) is now responsible for defining and monitoring compliance. The concerned entities must self-assess over two years and demonstrate compliance to the ElCom. If measures are not promptly implemented, the ElCom engages with companies. In justified cases, an extension may be exceptionally granted.

Surveillance Role of the ElCom

Under Article 22, paragraph 1 of the LApEl, the ElCom monitors compliance with OApEl provisions and related ordinances. Thus, the ElCom now has a specific mission in the cybersecurity framework for Swiss electricity actors:

- Monitoring: The ElCom monitors compliance with cyber protection measures using the NIST cybersecurity framework and minimum legislative requirements.

- Investigation: In its monitoring process, The ElCom uses self-assessment surveys to document companies’ cybersecurity practices.

- Awareness Interviews: The ElCom conducts awareness interviews with companies deemed crucial for network security and stability.

- Audits: The ElCom can conduct targeted audits in response to anomalies identified during surveys or interviews or based on external indications.

Legal Compliance Timeline

Legal Compliance Timeline

Expected Maturity Levels

The revised OApEl defines three protection levels (A, B, C) to ensure cybersecurity measures are proportional to the potential impact on the Swiss ecosystem. Each level has specific measures and sets expectations for NIST maturity scores (/4).

Membership to each level is proportionate to the volume of electricity produced and/or distributed by network managers and their providers, as well as by producers (excluding nuclear), storage operators, and their providers:

- Level A: More than 450 GWh/year (operators) or more than 800 MW (producers)

- Level B: Between 450 and 112 GWh/year (operators) or between 800 and 100 MW (producers)

- Level C: Less than 112 GWh/year (operators) or less than 100 MW (producers)

Each level has expected maturity scores for NIST control points. For example, for NIST ID-AM 2 (Develop a process for inventorying and continuously maintaining a comprehensive list of your ICT equipment), a NIST maturity level of 4/4 is expected for level A, 3/4 for level B, and 2/4 for level C.

Analysis

A detailed analysis of OApEl expectations reveals five particularly critical areas, and four others that may appear surprisingly low given the sector and associated risks.

Major compliance points (highest expected scores)

- Governance

- Access Management

- Awareness and Training

- Protection and Security Solutions

- Risk Analysis

Minor Compliance Points (Lowest Expected Scores)

- Communication during and after an incident

- Detection and Investigation

- Mitigation and Isolation

- Business Environment

It is recommended for affected organizations not to neglect preparation for incident communication, response, and isolation capabilities. These elements are crucial for the sector’s criticality to the Swiss economy and the need for operational cooperation for effective crisis management.

Conclusion

With the revision of OApEl, Switzerland’s legal framework gains a new binding sectoral text that will push market actors in the electricity sector to meet expected maturity levels as set by this new regulation.

In perspective with the CySec Rail directive and Finma circulars, Swiss cybersecurity is becoming standardized at the national level, although the texts remain disparate. Indeed, OApEl mainly relies on NIST via the Minimum ICT Standard, while the CySec Rail Directive (for railways) combines elements from ISO 2700X and NIST, and Finma circulars (for the financial sector) formalize sector-specific requirements.

Consequently, it is not unimaginable that other sectors will be impacted soon.