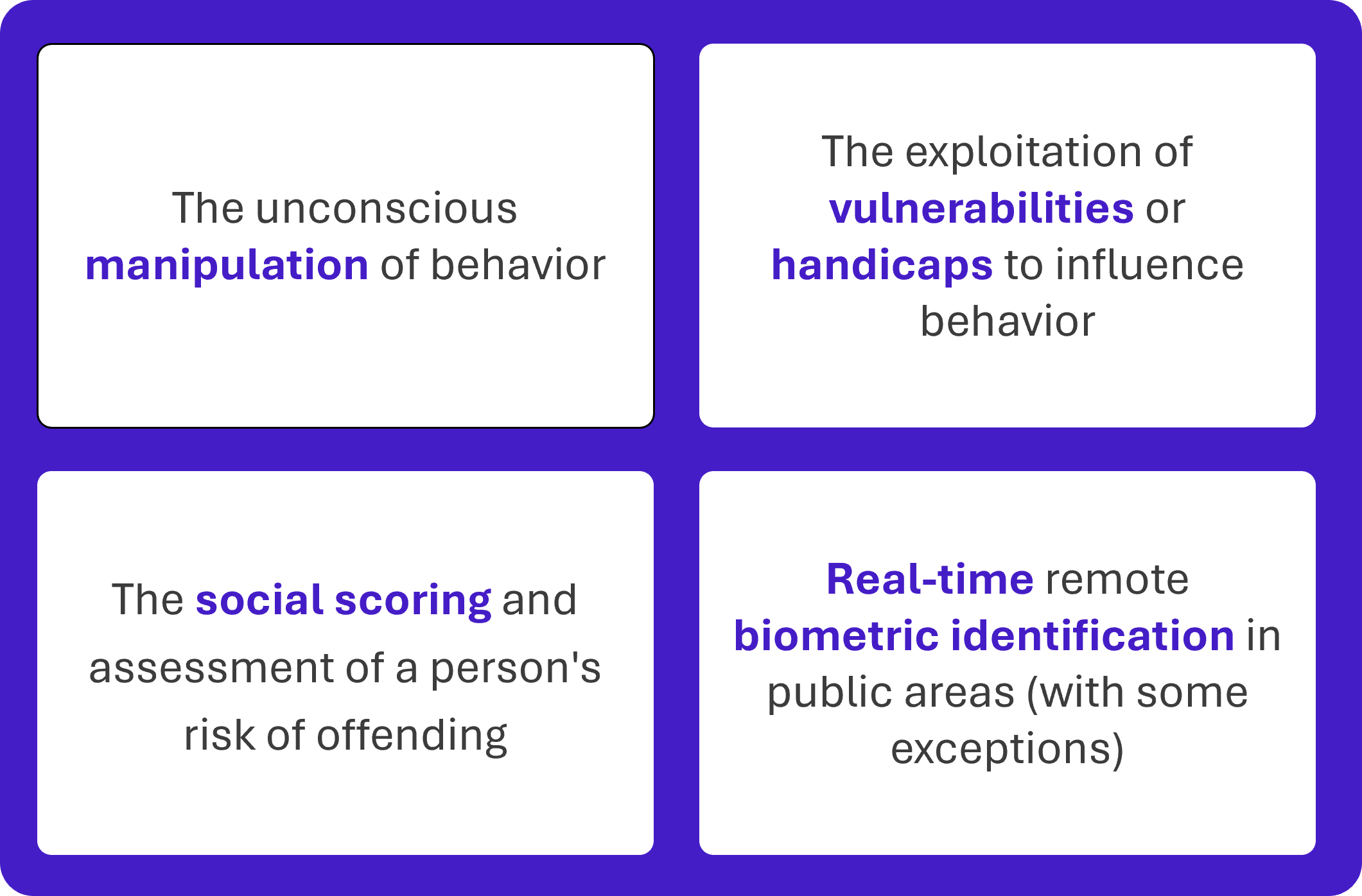

Here we are, on May 21, 2024, the European regulations on AI see the light of day after 4 years of negotiations. Since February 2020, the European Union (EU) has been interested in Artificial Intelligence Systems (AIS) with the publication of the first white paper on AI by the European Commission. Four years later, on March 13, 2024, the European Parliament approved the regulation on artificial intelligence (AI Act) by a large majority of 523 votes out of 618 and Europe became the first continent to set clear rules for use of AI.

To arrive at this favorable vote, the European Parliament had to face heavy opposition from lobbyists, in particular certain AI companies, which, until now, could benefit from a very large panel of training data, without worrying about Copyright. Some governments, like French, have also tried to block it the act. In the case of the French State, they feared that regulations could slow down the development of French Tech.

On December 9, 2023, the Parliament and the Council agreed on a text, after three days of “marathon talks” and months of negotiations. An almost record number of 771 amendments were integrated into the text of the law, this is more than required for the passing of GDPR, which displays the difficulties encountered in the adoption of the AI Act.

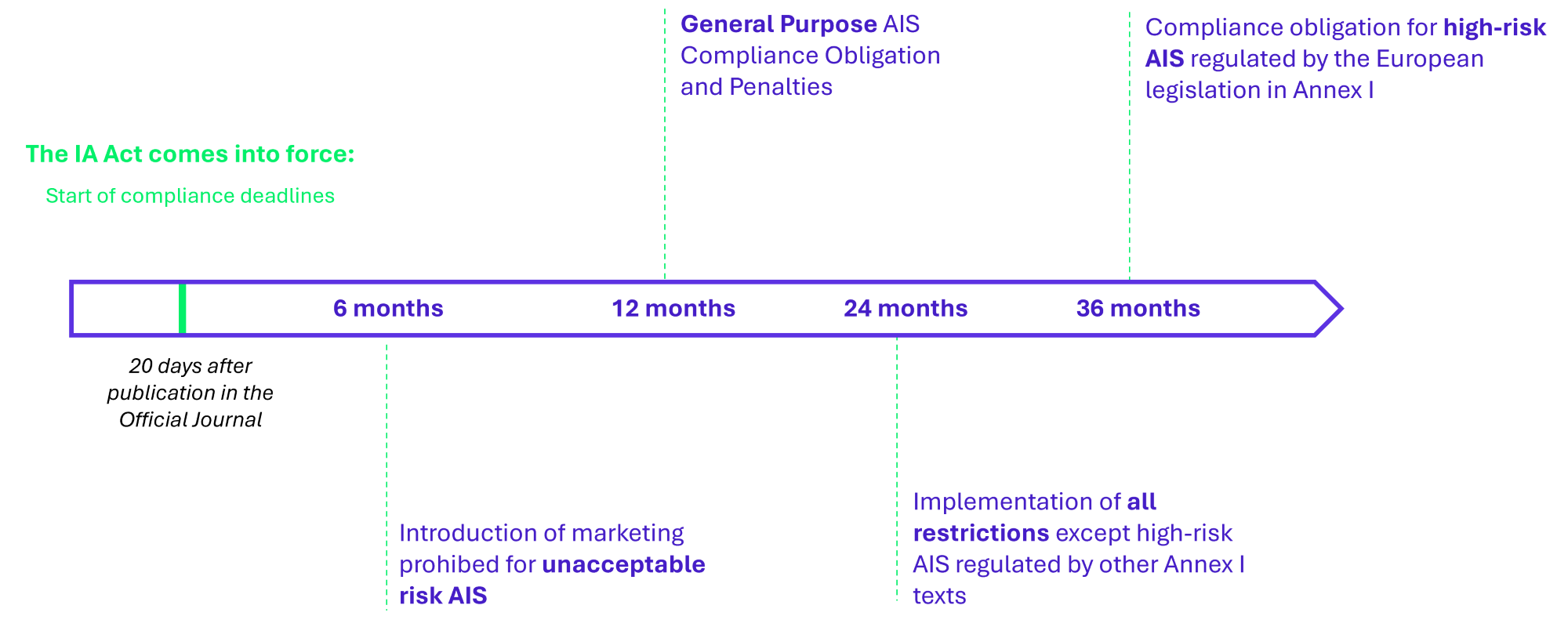

The regulation on artificial intelligence (AI Act) was approved on March 13, 2024 by the European Parliament, then on May 21, 2024 by the European Council. This is the final step in the decision-making process, paving the way for the implementation of the act. As it is a regulation, it is directly applicable to all EU member countries. The next deadlines are given in Figure 6, at the end of this article.

Figure 1: Timeline of adoption of the AI Act

Who are the stakeholders and supervisory authorities?

The AI Act essentially concerns five main types of actors: suppliers, integrators, importers, distributors, and organizations using AINaturally, suppliers, distributors, and user organizations are the most targeted by regulation.

Each EU state is responsible for “the application and implementation of the regulation” and must designate a national supervisory authority. In France, the CNIL could be a good candidate[1] which created, in January 2023, an “Artificial Intelligence Service”.

A new hierarchy of risks that brings cybersecurity requirements.

The AI Act defines an AIS as an automated system that is designed to operate at different levels of autonomy and that, based on input data, infers recommendations or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.

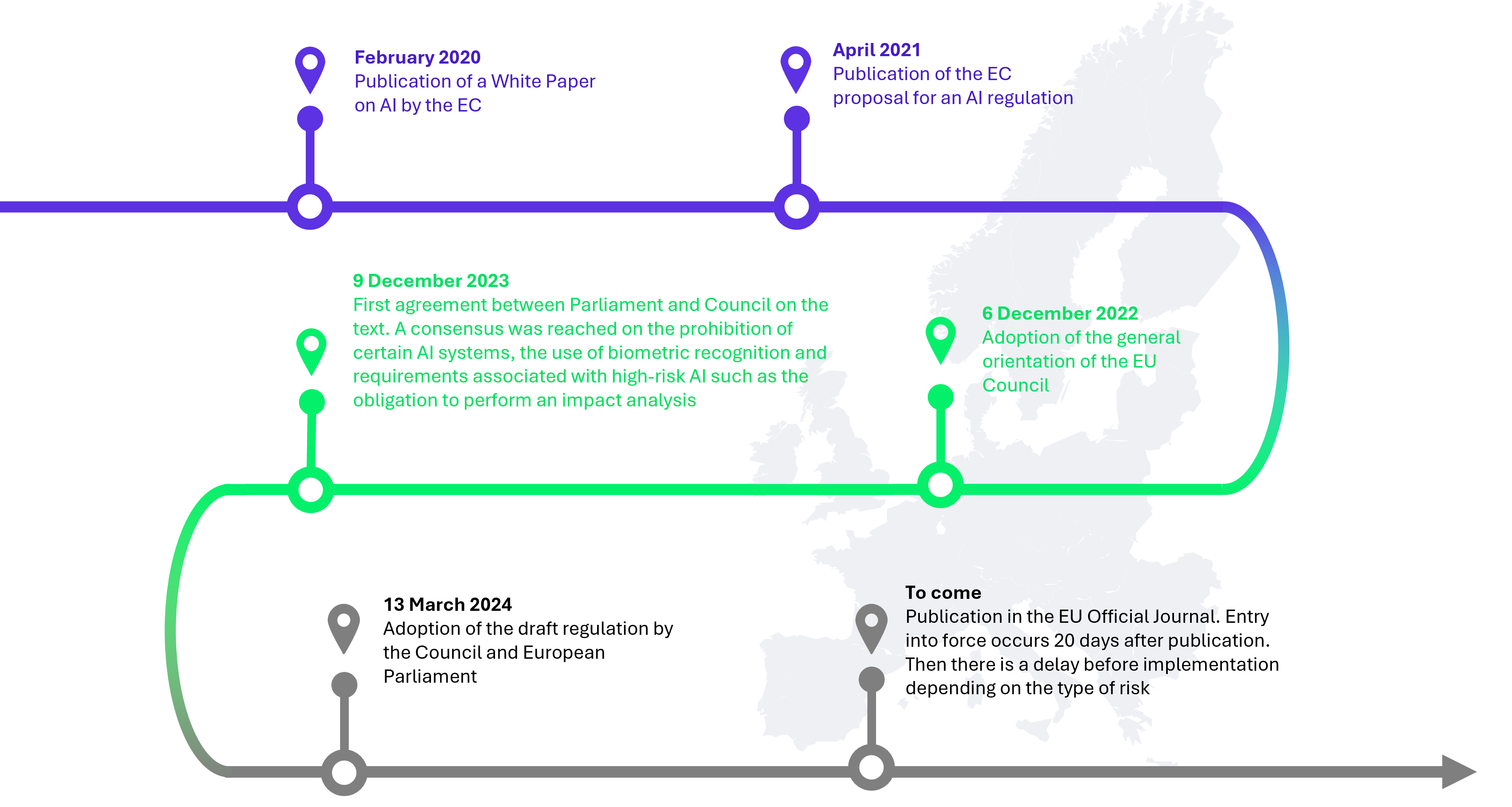

AISs are classified into four levels according to the risk they represent: unacceptable risks, high risks, limited risks, and low risks.

Figure 2: Risk classification, requirements and sanctions

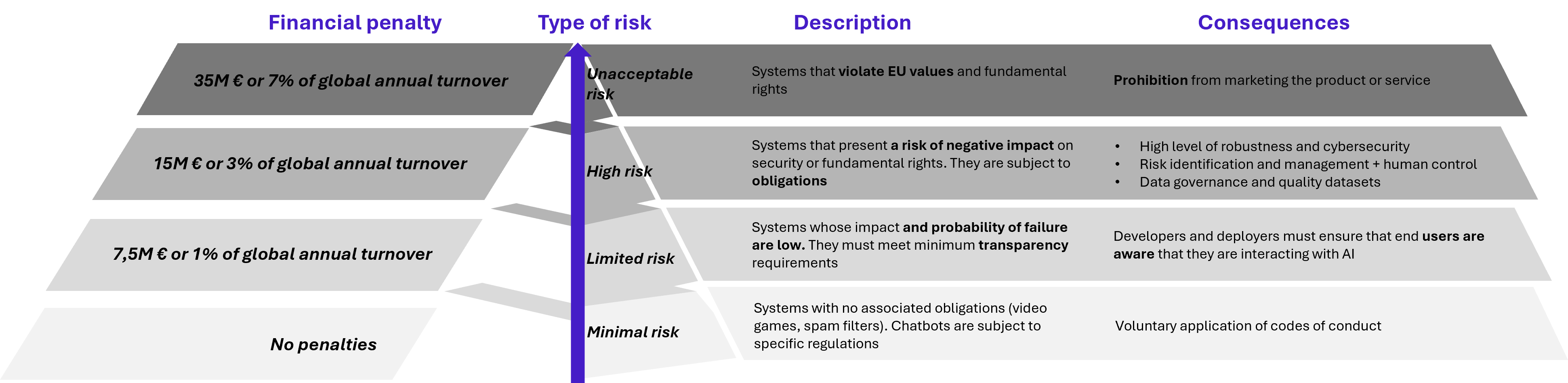

- AISs at unacceptable risk are those generating risks that contravene EU values and undermine fundamental rights. These AISs are quite simply prohibited; they cannot be marketed within the EU or exported. The various risks deemed unacceptable and therefore leading to an AIS being prohibited are cited in the figure below. Marketing this type of AIS is punishable by a fine of 7% of the company’s annual turnover or €35 million.

Figure 3: Use cases of unacceptable risks

- High risk AISs present a risk of negative impact on security or fundamental rights. These include, for example, biometric identification or workforce management systems. They are the target of almost all of the requirements mentioned in the text of the AI Act. For these AISs, a declaration of conformity and their registration in the EU database are required. In addition, they are subject to cybersecurity requirements which are presented in Figure 4. Failure to comply with the given criteria is sanctioned at a maximum of 3% of the company’s annual turnover or €15 million in fine.

- Limited risk AISs are AI systems interacting with natural persons and being neither at unacceptable risk nor at high risk. For example, we find deepfakes with artistic or educational purposes. In this case, users must be informed that the content was generated by AI. A lack of transparency can be penalized at €7.5M or 1% of turnover.

- Low risk AISs are those that do not fall into the categories cited above. These include, for example, video game AI or spam filters. No sanctions are provided for these systems, they are subject to the voluntary application of codes of conduct and represent the majority of AIS currently used in the EU.

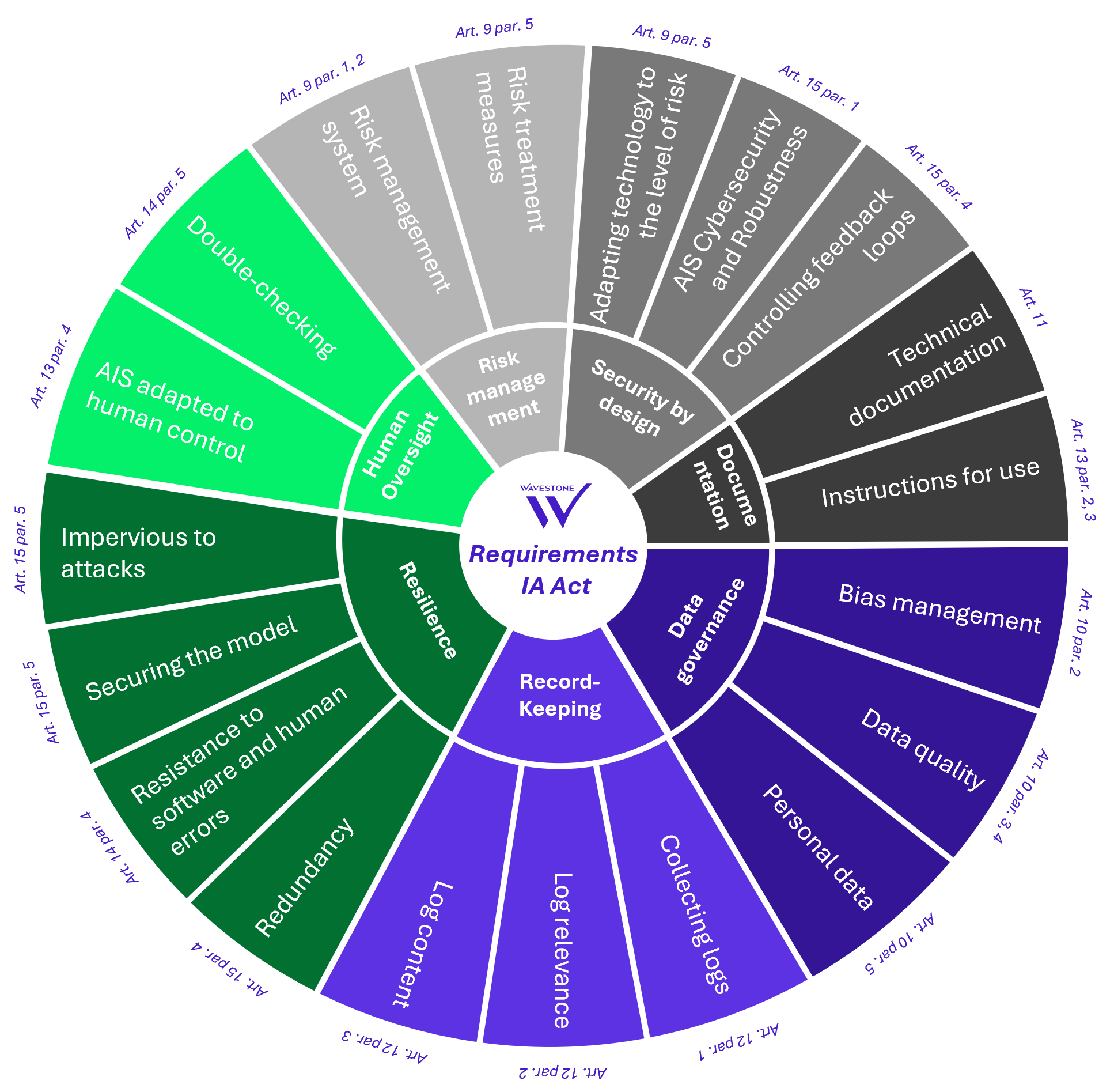

Cybersecurity requirements addressed to high-risk AISs.

Although the AI Act Regulation is not solely focused on cybersecurity, it sets a number of requirements in this area:

Figure 4: The AI Act’s cybersecurity requirements

We have identified seven main categories:

Risk Management: The text imposes, for high-risk AISs, a risk management system which takes place throughout the life cycle of the AIS. It must provide, among other things, for the identification and analysis of current and future risks and the control of residual risks.

Security by Design: The AI Act requires high-risk AISs to take into account the level of risk. Risks must be reduced “as much as possible through appropriate design and development”. The regulation also mentions the control of feedback loops in the case of an AIS which continues its learning after being placed on the market.

Documentation: Each AIS must be accompanied by technical documentation which proves that the requirements indicated in Annex 4 of the law are respected. In addition to this technical documentation addressed to national authorities, the AI Act requires the drafting of instructions for use that can be understood by users. It contains, for example, the measures put in place for system maintenance and log collection.

Data Governance: The AI Act regulates the choice of training data[2] on the one hand and the security of user data on the other. Training data must be reviewed so that it does not contain any bias[3] or inadequacy that could lead to discrimination or affect the health and safety of individuals. This data must be representative of the environment in which the AIS will be used. For the protection of personal data, the resolution of problems linked to bias (presented earlier), to the extent that it cannot be handled otherwise, serves as the only exemption for access to sensitive data (origins, beliefs policies, biometric or health data, etc.). This access is subject to several confidentiality obligations and the deletion of this data once the bias is corrected.

Record Keeping: Automatic logging is part of the cyber requirements of the AI Act. The latter must, throughout their life cycle, identify the relevant elements for the identification of risk situations and to enable the facilitation of post-market surveillance.

Resilience: The AI Act requires high-risk AIS to be resistant to attempts by outsiders to alter their use or performance. The text emphasizes in particular the risk of “poisoning” of data[4]. Additionally, redundant technical solutions, such as backup plans or post-failure safety measures, must be integrated into the program to ensure the robustness of high-risk AI systems.

Human Monitoring: The AI Act introduces an obligation for human monitoring of AIS. This begins with a design adapted to human surveillance and control. Then, it is required that the design of the model ensures that no action or decision is taken by the deployment manager without the approval of two competent individuals, with a few exceptions.

The new case for general-purpose AI: specific requirements.

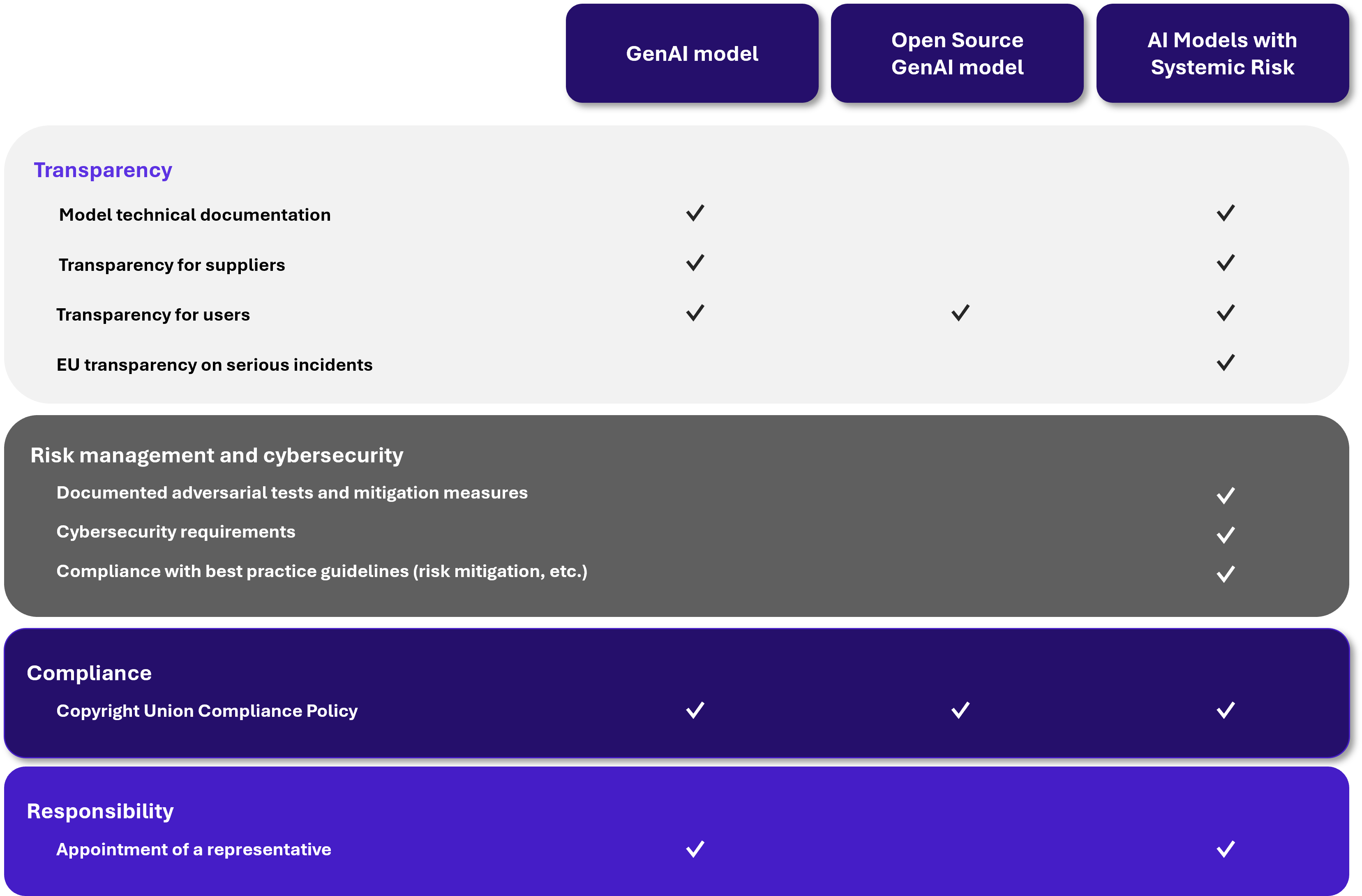

Since the April 2021 bill, negotiations have led to the appearance of a new term in the regulation: that of Gen AI or “general purpose AI model”. The latter is defined in the text as an AI model that exhibits significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks. These models form a very distinct category of AIS and must meet specific requirements. The new chapter V of the regulation is dedicated to them. There are mainly bonds of transparency towards the EU, suppliers and users as well as respect for copyright. Finally, suppliers must designate an agent responsible for compliance with these requirements. But the new version of the AI Act also introduced a new concept: that of Gen AI with “systemic risk”, which are the most regulated.

What is systemic risk Gen AI?

The AI Act defines “systemic risk” as “a high-impact risk of general-purpose AI models, having a significant impact on the European Union market due to their scope or negative effects on the public health, safety, public security, fundamental rights or society as a whole, which can be spread on a large scale.” Concretely, a Gen AI is considered to present a systemic risk if it has a high impact capacity according to the following criteria:

- A quantity of calculation used for its training greater than 10^25 FLOPS[5] ;

- A decision by the Commission based on various criteria defined in Annex XIII such as the complexity of the model parameters or its reach among businesses and consumers.

What measures should be implemented?

If the AIS falls into these categories, it will have to comply with numerous requirements, particularly in terms of cybersecurity. For example, Section 55(1a) requires providers of these AISs to implement adversarial testing of models with a view to identifying and mitigating systemic risk. In addition, systemic risk Gen AIs must present, in the same way as high-risk AISs, an appropriate level of cybersecurity protection and protection of the physical infrastructure of the model. Finally, like the GDPR with personal data breaches, the AI Act requires, in the event of a serious incident, to contact the AI Office[6] as well as the competent national authority. Corrective measures to resolve the incident must also be communicated.

The following diagram summarizes the different requirements based on the general-purpose AI model:

Figure 5: The requirements of the different GenIA models

Is it possible to ease certain requirements?

In the case of a general-purpose AI model that does not present systemic risk, it is possible to significantly reduce the obligations of the regulation by making it free to consult, modify and distribute (Open Source[7]). In this case, the provider is obliged to respect the copyrights and to make available to the public a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used to train the AI model.

On the other hand, a Gen AI with systemic risk will necessarily have to respect the requirements set out above. However, it is possible to request a reassessment of your AI model by proving that it no longer presents a systemic risk in order to get rid of the additional requirements. This re-evaluation is possible twice a year and is validated by the European Commission on objective criteria (Annex XIII).

How to prepare for AI Act compliance?

To prepare well, you should respect the risk-based approach which is imposed by the text. The first step is to do the inventory of its use cases, in other words, identify all AISs that the organization develops or employs. Secondly, it is about classifying your AISs by risk level (for example through a heat map). The applicable measures will then be identified according to the risk level of the AIS. The AI Act also requires the implementation of a security integration process in AI projects which allows, as with any project, to assess the risks of the project in relation to the organization and to develop a relevant plan to remediate these risks.

To initiate compliance with applicable measures, it is appropriate to start by updating existing documentation and tools, in particular:

- Security Policies to define requirements specific to AI security;

- Evaluation questionnaire the sensitivity of projects targeting questions relevant to AI projects;

- Library of risk scenarios with attacks specific to AI;

- Library of security measures to be inserted into AI projects.

What are the next steps?

Figure 6: Implementation timeline of the AI Act

—

[1] The CNIL and its European equivalents could use their experience to contribute to more harmonized governance (between Member States and between the texts themselves).

[2] Training data: Large set of example data used to teach AI to make predictions or decisions.

[3] Bias: Algorithmic bias means that the result of an algorithm is not neutral, fair or equitable, whether unconsciously or deliberately.

[4] Data poisoning: Poisoning attacks aim to modify the AI system’s behavior by introducing corrupted data during the training (or learning) phase.

[5] FLOPS: Unit of measurement of the power of a computer corresponding to the number of floating point operations it performs per second, for example, GPT-4 was trained with a computing power of the order of 10^ 28 FLOPs compared to 10^22 for GPT-1.

[6] AI Office: European organization responsible for implementing the regulation. As such, he is entrusted with numerous tasks such as the development of tools or methodologies or even cooperation with the various actors involved in this regulation.

[7] Open Source: AI models that allow their free consultation, modification and distribution are considered under a free and open license (Open Source). Their parameters and information on the use of the model must be made public.