Yesterday, the team YoloSw4g from Wavestone’s Cybersecurity practice took part in the 2022 Defcamp CTF finals. Defcamp is one of the top cybersecurity conference in Europe and every edition is hosted in Bucharest, Romania. Wavestone had the opportunity to play the CTF and finals for the two previous editions, and the format and quality of challenges have always been appreciated. Unlike previous editions where the format was Jeopardy (a list of challenges to solve that each bring points), this year was Attack/Defense.

The attack/defense (A/D) format

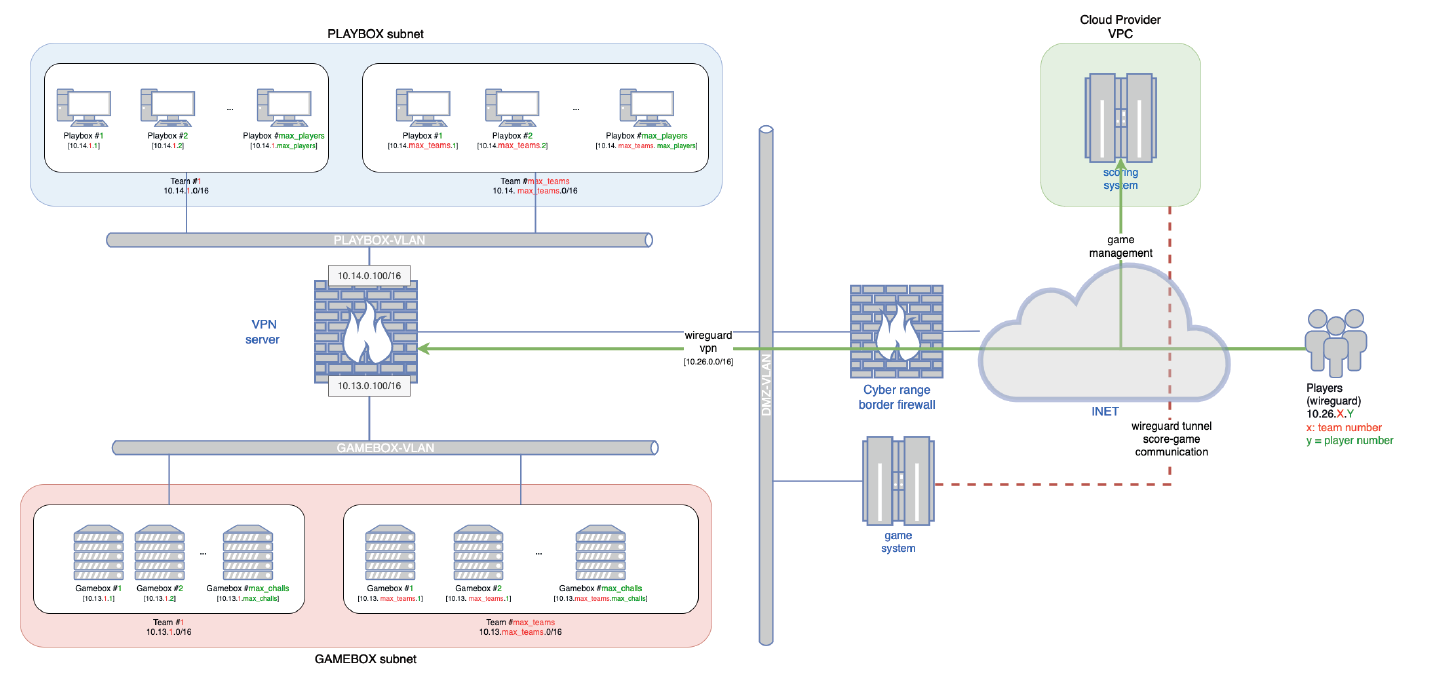

During this the A/D exercise, teams have literally been competing against each other, on the 10AM – 7PM slot, with the 10AM-11AM slot dedicated to hardening rather than attack. Each teams had two virtual machines that were running a variety of services:

- The first VM hosted services in Docker containers: songs/singers management webapp, auction website, binary application to emulate a business service, etc.

- The second VM offered services directly on the host, through services and workers ran by dedicated users: CVE search website, remote control webapp, etc.

The services had been intentionally modified to include vulnerabilities, misconfigurations and backdoors that can be exploited. Upon exploitation, for each service there was a flag file that could be stolen to bring points to the exploiting teams, and remove points from the victim. Flags were renewed every two minutes by the organizer’s bot, so teams were gaining and losing points as long as the services remained vulnerable.

There were also misconfigurations in the Docker containers and on the host that allowed for lateral movement between the services, escape from the containers and even privilege escalation to root for complete takeover and persistence.

Finally, to provide a kind of realism for the exercise, the teams had to keep the services operating or they would lose SLA points. Preventing the organizers to renew or read the flags also result in point loss.

Given the nature of the exercise, the teams were encouraged to patch their services during the CTF to remove the vulnerabilities. However, in doing so it was easy to damage a feature of the service and to lose points in the process: since the SLA checks were not documented, there was no way at first to know if we could remove the vulnerable part of the application or if we had to spend time to keep it running.

Let’s talk strategy!

In this CTF format, there are few valid strategies to try and win the 1st place:

- Focus on attack: there are many other teams so while they remain vulnerable, a single exploit could provide access to many flags and points

- Focus on defense: if the services are correctly patched and no persistence is established, it is easier to later focus on how to exploit while preventing point loss

- Split the team to do a little bit of both

The attack strategy

The teams had one hour before the opening of the network links between each other, so this had to be spent to analyze their own services. The goal at this point is to quickly identify vulnerabilities that can be exploited in a few lines of codes, so configuration and code review is key:

- The little-known grep tool that allows for identification unsafe of function use (for example shell_exec and system in PHP, execSync in NodeJS, etc.)

- The LinPEAS / Linux-Smart-Enumaration open-source tools to find misconfigurations on the hosts

Due to the fact that security issues had mainly been voluntarily introduced in the applications rather than embedded within the codebase in a complex way, this strategy is efficient: calls to vulnerable functions can easily be traced back to URL and API endpoints with few prerequisites for exploitation.

However, the downside is that exhaustivity is hard: the codebase and amount of misconfigurations is high enough not to find them in one hour. And with webshells appearing everywhere once the exercise starts, searching for code execution functions or public keys is not always representative.

The defense strategy

This strategy is really all about preventing point loss rather than making points. On the long term, teams gain more points by exploiting the services than losing from not patching them, so it is not a viable strategy for the whole CTF.

The teams had been informed a couple weeks ago by the organizers about the nature of the exercise and on some details of the infrastructure. Therefore, teams had some time to prepare defense mechanisms, although the exact nature of challenges was not really known.

We also figured that visibility was key, for a lot of reasons: finding the nature of SLA checks, detecting exploit attempts, detecting flag leaks or communication with other teams infrastructure. In this effort, the following tools can be used to observe what’s happening in the infrastructure:

- At the system level: auditd, and if motivated forwarding logs to a SIEM instance to automatically detect strange behavior

- At the application level: Apache logs and mod_security to find execution errors, malicious payloads and also block some of the attempts

- At the network level: tcpdump, tshark and Wireshark, which give the most insight on the other teams’ activity towards our own infrastructure, but is limited by encrypted protocols and volumetry of traffic

The “why not both” strategy

Teams were limited to 5 people onsite, so this strategy may be the most efficient, it is not really optimal given the conditions of this exercise. However, it is still what most teams do because it is hard to properly organize on-the-fly. However, it can be optimized by assigning players on both attack and defense on a single service rather than specializing them in attack or defense.

What we did in practical

During the pre-exercise phase, we thought that the ratio between binaries and web applications would be quite balanced, so we had to come up with protections for both:

- For binaries, most of the exploits use vulnerabilities to launch a shell to read the flag, or the chain open-read-write operations to print the flag contents on the standard output. We tried to rely on the SECCOMP kernel feature that mimics a firewall logic (based on the BPF technology) to allow or prevent some system calls and apply constraints on their arguments: the goal here was to learn about that normal behavior, and block all deviations, either execve system calls to launch a shell or open system calls on the flag file.

- For web applications, we thought that deploying Apache mod_security was a good compromise in terms of setup complexity, gain in visibility and basic exploit prevention. We also came up with a list of functions that could be used in a malicious way, such as system, shell_exec, eval and so on.

- Finally, since we knew there would be Docker containers, we thought about ensuring that none of them were too privileged to allow for container escape and host compromise.

Finally, we knew about the flag system and the frequency of flag change, so we designed a Python orchestrator to run exploit scripts, collect flags, and submit them to the validation platform.

On D-Day, during configuration review on the hosts, we noticed that SECCOMP had been disabled at the kernel level, so our winning strategy took its first hit. However, there was only 1 binary for 6 web applications, so its efficiency would have been limited.

We spent the first hour trying to identify the quick win vulnerabilities and found some of them. We swiftly developed scripts to exploit them with our orchestrator and thought that we were ready for the opening of communication between teams. We were not. Almost half of the teams had patched the vulnerabilities we had found, and many of them were stealing flags we thought we had patched vulnerabilities for. We realized at this point that for each flag there would be many more vulnerabilities leading to their theft.

We quickly decided to increase our visibility on the situation by running tcpdump and analyzing the traces with Wireshark and what we observed was a lot of different exploits. Patching the issues was not as easy as initially thought due to the potential number of entry points and the impact of the patches on the services. However, by looking at other people exploits, we were able to replicate them and launch them at other teams to compensate for the points that we were loosing.

At one time, we noticed that one of our exploits, which should have been working, did not. We had code execution on a server, but it was impossible to read the flag files: the team had found a way (which was borderline anti-game in our mind, but still) to make the flag unreadable by the vulnerable services and only to the organizers. This lead us to tighten the host security by focusing on least privilege strategy:

- The flags should in theory not be read by more than the user launching the service and the organizer’s account

- Teams were actively exploiting one service to dump all flags at once

- Therefore, we decided to create new groups on the host restricted to these users, and make the flags unavailable to other service accounts

This became quite efficient, and the visibility we gained gave us much insight and what could be exploited and what needed to be patched. Due to our hardening actions, we had finally reduced the amount of points lost due to flag stealing, so we had time to focus on creating exploits, some of them quite basic, but which worked on almost half of the teams until the end!

Two or three hours before the end, a few teams managed to break out of the containers and services to get root permissions on other teams boxes. They quickly began to install persistence, create flag stealing scheduled tasks, and perform binary backdooring. At this point, at every tick of the exercise, they were stealing all four flags from each VM effortlessly which gave them lots of points, locking the podium away. Like in real-life, it becomes very complex to eliminated the persistence due to the simplicity of reinstalling it in opposition to the number of entry points to patch.

Our strategy designed on-the-fly still granted us the 4th place, which was a nice surprise for us:

Takeaways

We really did appreciate the format of the exercise and its quality. It was a welcomed change from the standard jeopardy format we had been playing for years and it forced us to think differently. In some ways it was much closer to our pentester / incident responder daily jobs:

- Sometimes we have to focus on impacting vulnerabilities rather than exhaustivity, for example during red team assignments from the Internet

- It gave us insight on the complexity of patching vulnerable applications in a limited timeframe with limited to no impact on its business features

- It highlights the effect of stress during situations such as cyber crisis where organization between actors is the key factor, but too often neglected in favor of other seemingly important actions

However, if we take a step back, we also noticed that:

- The complexity of organizing such an event is really high: the system and network infrastructure would need to be perfect in every way for it to work as intended. But there are always unplanned issues and bugs which allow for bypassing some of the game’s rules and the limit between fairness and antigaming is often blurry.

- Due to the limited time of the exercise, we almost never had the time to implement recommandations that we would communicate to our clients after a pentest. There were too many hotfixes with limited efficiency and even more limited clarity.

I would like to conclude this article by really thanking all the actors involved in this event:

- The organizers Defcamp team and CyberEdu for setting up this exercice

- The other teams, for letting us exploit their vulnerabilities and for coming up with always inventive exploits, patches and backdoors

- My colleagues from YoloSw4g team: Maxime MEIGNAN, Gauthier SEBAUX, Thomas DIOT, Yoann DEQUEKER

- All CTF players from Wavestone who keep the team alive and allow us to participate in these competitions

Jean MARSAULT