[nota bene: this article has been translated to English for accessibility reasons. It does not address UK or US regulations, but only French ones regarding Security Accreditation (“homologation” in French). It is nonetheless useful for any organization wanting to implement security accreditation in Agile projects.]

“Security accreditation is a formal act by which the authority responsible for a system commits its responsibility to risk management.” [1]. It is of course mandatory in some cases[2], but beyond that, it is also a way of sending a strong message to users and top management: security is indeed a major topic for the organization. Agile methodology was at first designed for projects, but it can be a real opportunity for security teams to reduce security risks.

This method disrupted working habits of product teams and ISS teams (Information System Security). The latter have to find a way to go beyond adapting old accreditation method and propose a new relevant solution to still comply with the original goal of the accreditation: “Find a balance between acceptable risk and security costs, then have it formally accepted by a manager/an authority who has the power to do so[3]”.

One solution: provisional accreditation and long-term accreditation

As a famous Agile Security expert from Wavestone once said: “Agile and accreditation, it’s not rocket science”. Without denying the difficulties, explaining it is quite simple. Faced with teams that must deliver faster and provide continuous releases, the risk levels and therefore the security accreditation must be dealt with at the same pace.

What should the accreditation consider?

As always, security accreditation is all about giving thorough information on a project’s security risk level to the Accreditation Authority, for them to decide if it’s acceptable with regard to the organization ISS criteria (e.g. number of EUS still on the backlog, percentage of security baseline rules implemented on a given scope, etc.). Then, they take responsibility for the possible residual risks.

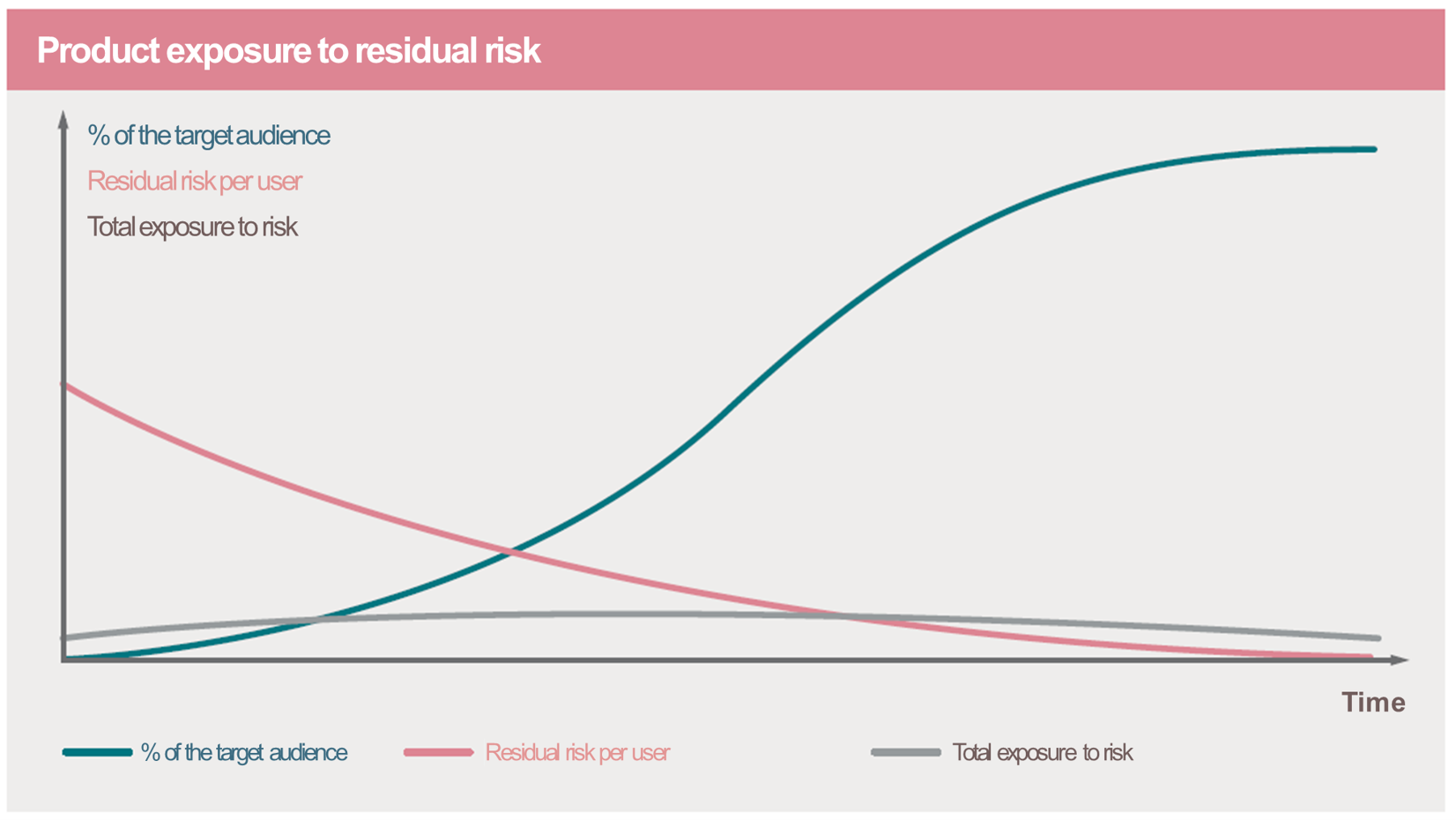

For example, only a few features are available to a few users at the beginning of a project. This small scope will display a lower level of risk (because of a low level of exposure) despite not being fully secured yet. Provisional accreditation (for a few months for example) may be issued to allow experimentation. It will have to be renewed when renewal criteria (defined in advance) are met.

Figure 1 – Product exposure to residual risk

From the ANSSI guide (in French): Digital Agility and Security, October 2018 (link to the guide)

For a project at cruising speed, accessible to its target audience with all the expected features, a firm accreditation (3 years for example) is pronounced. The criteria for renewal, leading to the issuance of a new accreditation, are also defined in advance.

When to renew the accreditation?

The criteria used to know when to renew the accreditation are closely linked to the project, the context, or the scope, but here are some examples to build these criteria. The provisional accreditation is valid until:

- New critical features are added (“critical” depending on the project),

- A new threshold for the number of users has been reached (defined in advance, depending on the associated risks),

- New personal data must be integrated and processed by the project,

- New features related to payments must be implemented,

- A new level of transaction volume is reached,

- And of course when the accreditation deadline is reached.

Long-term accreditation is valid for a longer time because less changes are expected at this stage of the project. That being said, the accreditation will have to be renewed regularly (at least every 3 years) to check on security levels and in a will of continuous improvement.

What evidence should squads bring?

Squads/feature teams should be able to bring different types of evidence/proofs (of the security level) to the Accreditation authority/responsible for the accreditation. The Evil User Stories (EUS) serve as what we used to call risks, where prioritization gives information about their criticality (see our article on how to lead a workshop on risk analysis in Agile). An extract from the backlog can be used as proof that the main EUS have been processed and that residual EUS are known (and accepted by the Accreditation Authority).

The Security Form (or Passport, detailed in this article on Agile transformation – in French -) is also a relevant way to follow-up on security levels of projects.

Code review and vulnerability scan reports can also be used (for squads that have integrated DevSecOps and have the appropriate tools).

If the X-team exists (see our article on the new ISS roles in Agile and the corresponding organization) or if an external audit team was able to perform them, the penetration test reports are also presented.

Any other existing documents can be used to give all necessary information (architecture documents, applicable regulations, etc.).

For provisional accreditation, these documents don’t have to be gathered in a proper “accreditation folder”, which would imply losing time for squads. What is necessary is to ensure they exist and are available to anyone involved in the accreditation process (accreditation authority or their delegate, ISS team, etc.).

Who are the actors in this process?

During product development, the Security Champion (see this article for definition) is in charge of organizing the risk analysis workshops (identification of EUS and associated Security Stories). The ISS team is of course involved in the process, bringing their knowledge to the squads during workshops.

The Product Owner is responsible for the creation and updates of the necessary documentation. They also make sure the ISS team is informed and asked for help when needed.

The accreditation Authority should be a business manager (e.g. the Business Owner) as usual. They must have the capacity to accept residual risks and validate the product security levels. As security should not slow down any Agile processes, the signing of a provisional accreditation may be delegated to the Product Owner, as they are representative of the Business Owner in the squad. The temporary accreditation can thus be signed faster if criteria for validity are met. In some cases, where projects would pose a risk to other businesses or systems, a transversal officer/business owner must be found, to sign for both businesses or systems. If no one is found, or no compromise is achieved, the Chief Information Officer (CIO) will assume responsibility, as it is their role to ensure the operational conditions of the Information System.

As a conclusion, security accreditation remains key when speaking about integration of security into projects, in particular within the Agile framework which changes the product teams’ way of working. The ISS teams must take advantage and (re)join these product teams (through the Security Champion and the security training of the product teams) and thus work together towards the incremental reduction of risk.

More articles to come on Agile Security, stay tuned!

[1] ANSSI guide (in French): Digital Agility and Security, October 2018 (link to the guide)

[2] (French regulations only) For administrations: decree n ° 2010-112 of February 2, 2010, terms of the General Safety Reference System (RGS). For any product dealing with information coming under National Defense secrecy: Interministerial General Instruction 1300. For operators of vital importance: cyber section of the LPM (law n ° 2013-1168 of 18 December 2013 – article 22), to strengthen the security of the critical information systems they operate, carried out as part of an accreditation process.

[3] ANSSI guide (in French): The nine steps of the security accreditation, August 2014 (link to the guide)