To say the least, cyber-resilience is a fashionable concept. The number of client requests on the topic has exploded this year: framing studies, program structuring, strategy definition, etc. Major accounts are currently multiplying initiatives. Paradoxically, the definition and scope of application of cyber-resilience is still unclear for most companies (for example, is cyber security included in cyber-resilience?). This article aims to shed light on the debate by providing some tips that have proven successful in the field.

Identification and mapping of key processes

Let’s start with a definition from the regulator: the European Central Bank defines cyber-resilience as the ability to protect oneself and to quickly resume activities in the event of a successful cyber-attack. This definition has led many companies to adopt a 360° vision on the topic (prevention, crisis management, reconstruction, business continuity, etc.) through the prism of a concrete cyber-attack on key business processes. The novelty lies above all in the fact that all the analysis is focused on critical business chains, even though it is still necessary to know them. Identifying and mapping key processes is often the most complex part of a Cyber Resilience Program. Unfortunately, there is no systematic method: a list drawn up by the Risk Department, a decision by the Director of Operations, recycling of business impact analyses (BIA), criteria established during regulatory audits, etc. One thing is certain, this list cannot be drawn up by the cybersecurity team in its own corner and requires the involvement of the business lines as early as possible in the process.

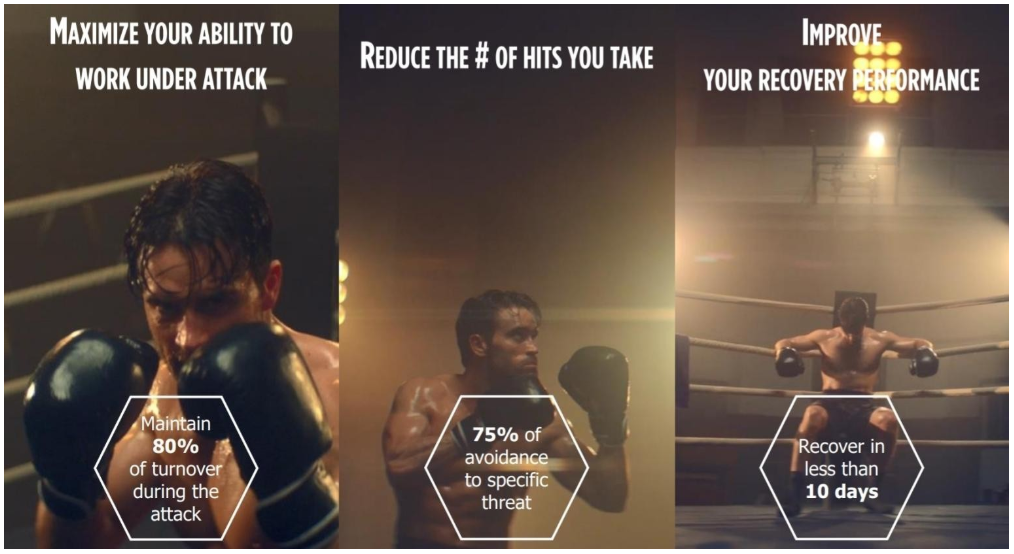

Analyzing the cyber-resilience of a business chain: the A.R.M. method

The cyber-resilience of a business chain can be improved by acting on several parameters: 1/ avoidance of the attack, 2/ rapid reconstruction, 3/ maintenance of business activity during the attack. As a result, many companies have structured their Cyber Resilience Program around 3 indicators: A (AVOID), R (RECOVER) and M (MAINTAIN), making it possible to target one threat at a time. Of course, most current initiatives are working on Ransomware scenarios (Ryuk, Maze, Sodinokibi, etc.).

A – AVOID

The first step is to assess the level of resistance of business chains to the feared cyber threats. The ATT&CK Framework is increasingly used here and this indicator can simply correspond to the percentage of techniques used by the attacker against which the business chain is protected (for example, the chain is protected against 60% of the attack techniques used by the ransomware groups of the moment). The level of assurance required differs from one company to another: even if most companies still work via self-declaration, it is possible to integrate a review of evidence or Redteam audits into the approach to make the results more reliable.

R – RECOVER

The second step requires assessing the reconstruction time of the business chain in the event of an attack (for example, the chain can be reassembled in 9 hours after a ransomware attack). This time can obviously be different from one attack to another: destruction often restricted to Microsoft systems, possibility to use backups or not, integrity checks necessary after reconstruction, etc. This requires a detailed analysis of the impacts of each attack studied. Be careful, when mapping, it is necessary to consider the reconstruction of ALL the assets impacted by the attack. It is often observed that a few specific assets can double or triple the overall reconstruction time. Here again, the level of insurance required differs from one company to another: it is possible to work on paper, but the real reconstruction test is clearly the best option for reassurance.

R – MAINTAIN

The last step requires assessing the ability of the business lines to work in a degraded mode before returning to normal. This is a purely business indicator, which obviously differs from one sector and chain to another: it can be a question of transactions, reception of parcels or number of passengers depending on the sector and the chosen chain. To calculate it, it is necessary to work with the business on the assumption of long-term unavailability of the critical chain and to evaluate the percentage of the activity that can be delivered in another way. To understand the approach in a theoretical, and deliberately provocative way: does a business process vulnerable to a cyberattack, but whose activity can be maintained without an IS for a few days, really need to increase investments in cybersecurity? This is the type of topic that a Cyber Resilience Program must be able to arbitrate.

Most Cyber Resilience Strategies and Programs on the market obviously embrace this recurring assessment phase, adding over the years cyber threats and business chains to be analyzed. At the same time, they are managing a series of cybersecurity, IT and business projects to increase the level of resilience. The most mature Programs also maintain catalogs of solutions to speed up the process and improve the scoring of the various business lines (data safes, standardized backups, market partnerships, shared business fallback solutions, etc.).

As we have seen, a cyber-resilience strategy involves multiple skills: the cybersecurity department to select threats and assess the robustness of chains, the business lines to select critical chains and work on business continuity, IT and the Business Continuity Plan (BCP) for crisis management and assessment of reconstruction capacities. The best solution is to host this type of Program directly at the Operations Department level, in order to influence all these channels. However, these Programs are currently structured at the level of the CISO or the Risk Management Department. The key in this case is to deploy effective governance that allows all stakeholders to remain within their area of expertise.