In a previous article, we saw that the Smart City was inducing a paradigm shift which, combined with the general public’s high expectations on the security of its data, required adapting the approach to such a project. Indeed, as the Smart City develops, urban activity becomes more and more dependent on its services, increasing not only its security needs, but also the interest of cyber attackers. Based on these observations, the challenge will therefore be to identify a new approach to take account of Cyber Security risks and, if not completely eliminate them, to reduce them. This is the purpose of this second article.

Building a Smart City project with Cybersecurity

It is essential to integrate cyber security aspects from the start of a Smart City project. Indeed, carrying it out later in the project may prove to be more complex and expensive, with the risk of not dealing with it / not being able to deal with all the risks.

This requires rethinking the organization of the project regarding data and security governance: security principles must be defined at the global project level and considered by each of the sub-projects composing the Smart City, depending on their constraints. This is particularly true as Smart Cities involve many actors with different core businesses, means and cybersecurity maturity. A global and shared vision is essential to ensure that each element processes the data with the appropriate level of security.

It is then necessary to define the main principles of architecture and interoperability, according to the constraints inherent to the Smart City, related to Edge Computing and the deployment of objects in a hostile environment. System resilience must be at the heart of safety requirements, as the fall or compromise of one element should not cause the entire system to fall.

To this end, common standards must be adopted, based on specific frameworks such as ETSI or OneM2M. These increase the chances of maintaining scalable interoperable systems. More generally, the NIST or the ISO 27002 standard are proven Cybersecurity frameworks on which it would be interesting to rely.

The development mode must be agile, integrating a long-term vision to anticipate new use cases, and with short milestones in order to quickly deliver the first services. Cybersecurity must be included in the development process, by defining Evil User Stories, enabling risks to be identified and considered each time services or the information system evolves, and by appointing cybersecurity experts in a support and validation role.

Defining and maintaining a satisfactory level of security will, more than ever, require the rigorous integration of security in all phases of the project, which may lead to greater but necessary human and technological investments.

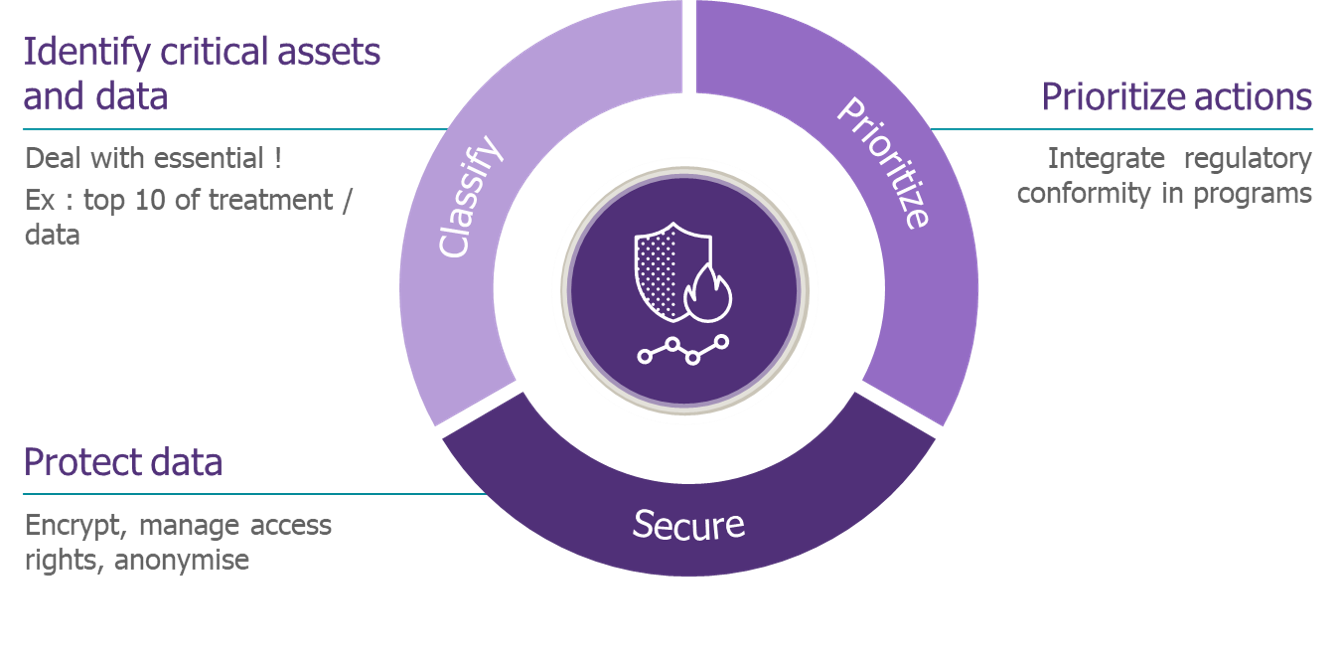

Protecting critical and regulated data

Given the propensity of the Smart City to collect and process large amounts of data, their protection will primarily involve identifying critical data and assets.

Most of the services offered by the Smart City are aimed at citizens. Therefore, personal and potentially sensitive data will be collected. Furthermore, a loss of availability or integrity of certain services could have serious repercussions since some components of the IS have a direct hold on the physical world. Smart Cities are not exempt from regulations, in particular the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), but also, depending on usage, from the General Security Regulations (GSR), the Military Programming Law (MPL) or the Network and Information Security (NIS) directive, whose data protection requirements will have to be integrated into the programs.

Levels of data sensitivity classification must therefore be formalized in order to enable the prioritization of actions and the setting up of an appropriate framework for the processing of critical data such as encryption and anonymization.

The problem of access to data should also be raised. There are many actors in the Smart City and it will be necessary to segment the “vision” they may have of the IS. This will involve a preliminary phase of defining the authorization profiles, necessary to respect the principle of least privilege, combined with a regular review of their assignments to ensure that they are still legitimate.

Operating in trusted environments

The Smart City project will necessarily rely on different technical and organizational foundations. If these bases are to the Information System what foundations are to a house, it is easy to understand that it will be difficult to build anything if this base is fragile.

As always, these technical bases must be covered by fundamental security measures: implementation of trust bubbles, hardening of systems, patch management, securing of privileged accounts and their use, etc.

Furthermore, an information system with a large attack area such as the Smart City will necessarily have to break with the traditional security model known as “castle security”, by relying more on aspects of partitioning and access control of the data itself. The conformity of assets within the information system will have to be continuously evaluated using common configuration and hardening frameworks. Exposed systems and applications must be subject to controls and audits, particularly during the development phase, but also during the operational phase.

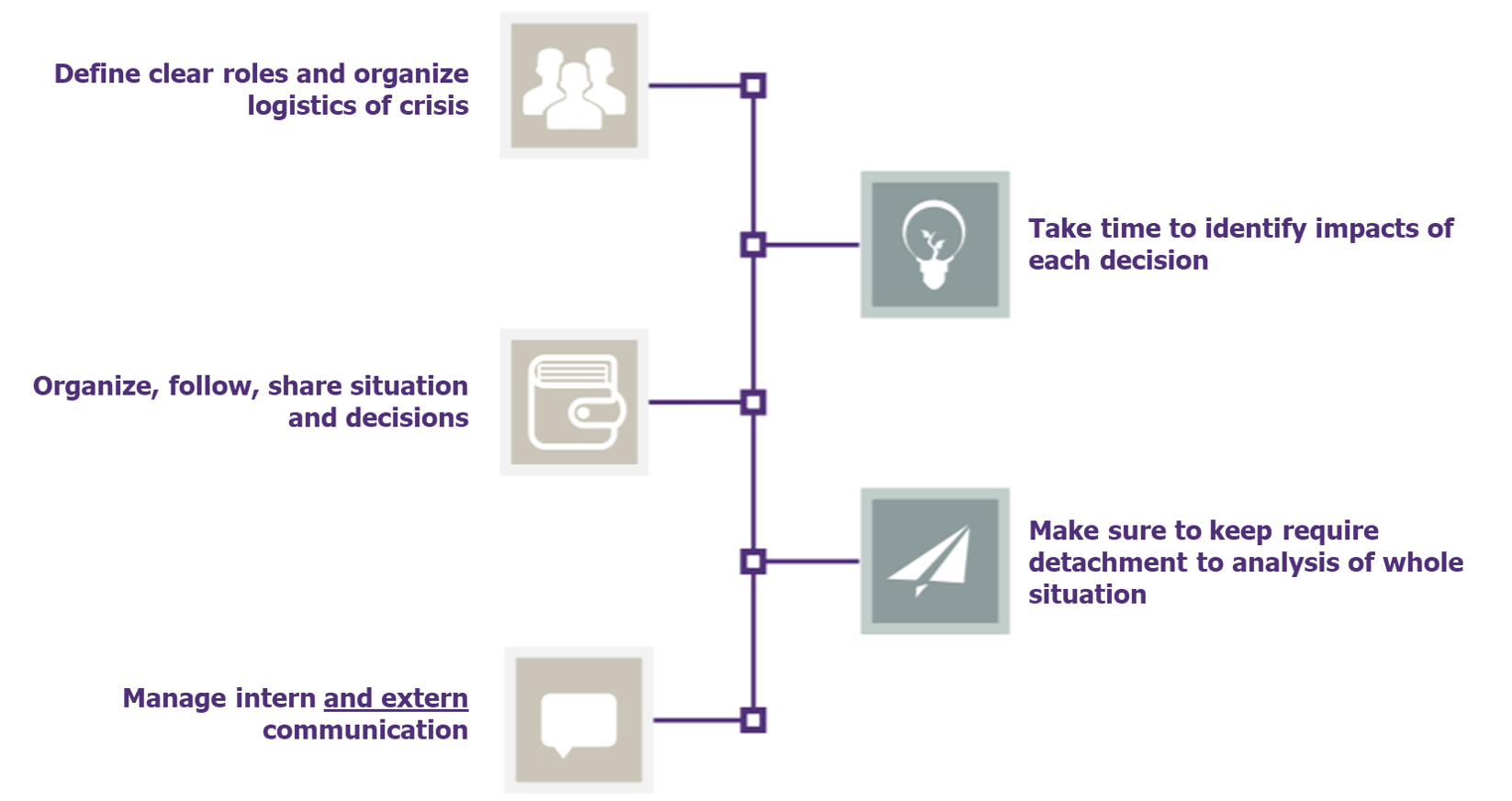

In addition, business continuity and disaster recovery will have to be at the heart of the security strategy. Plans will have to be formalized, but also tested, including both technical considerations such as the resilience of different systems, with the ability to restore systems independently of each other, and organizational considerations through crisis management exercises.

Finally, as Smart City involves many players, all stakeholders should ensure the implementation of significant means in the protection of the information systems involved and comply with the requirements of the project’s security policy. To do this, they will have to be contractually committed, at the very least by including security requirements in contracts, but also by formalizing and implementing security assurance plans, particularly for the most critical service providers. Regular controls may be commissioned to ensure that the security level is maintained over time and to address future risk scenarios.

Detecting, reacting and sharing

The Smart City cannot do without a service to detect and deal with security incidents.

It will be necessary to collect traces of activity on the systems and look for weak signals. In view of the large number of events to be processed, it will be essential to define the risks to be guarded against and to rely on correlation solutions to facilitate these searches. The use of automation tools will allow a first sorting of false positives, facilitating the work of analysts in the qualification of security alerts.

The detection and response service can be built using the PDIS and PRIS standards. Qualified external suppliers may be used for these two services as required.

The use of Cyber Threat Intelligence services will bring a significant efficiency gain in the creation and enrichment of SOC detection rules. Indeed, it will be possible to adopt a proactive detection posture by monitoring attacks that have targeted Smart Cities and the operating modes used. This will also have the advantage of improving the efficiency of the response service by saving precious investigation time.

Finally, the process of handling significant and major security incidents cannot be carried out without the formalization of a crisis management unit, composed of actors with well-defined roles and trained for this exercise. Particular attention will be paid to the external communication system, since the “severity” of a crisis depends as much on the event that caused it as on how it is perceived by the outside world.

In conclusion, and as we have seen through these two articles, the Smart City is a self-evident development in an era where demographic, ecological and economic issues are all intertwined. Its promises are seductive, but the implementation framework may give rise to some fears.

As with any digital transformation, ensuring a level of security in line with the challenges of the project will necessarily involve identifying the vulnerabilities and security risks it generates.

In the era of cyber-warfare and cyber-threats, the Smart City should be considered as a Digital Service Provider, within the meaning of the NIS directive, and be protected by security measures adapted to this status.

The provision of secure services, respectful of their users’ data, is a sine qua non condition for the success of a Smart City project, the benefits of which will only be matched by the magnitude of the impact of a successful cyberattack.