On January 31, 2017, President Trump postponed the signature of the Executive Order on cybersecurity, which was expected to lay the groundwork of the United States’ efforts to fight cyber threats in the coming years.

The presidential race was marked by a strong emphasis on cybersecurity. The topic, considered during the campaigns as “one of the most important challenges the next president is going to face” (Hilary Clinton, Derry, New Hampshire, February 3, 2016) and “an immediate and top priority,” (Donald Trump, Herndon, Virginia, October 3, 2016) was on the agendas of both final candidates, who expressed a strong willingness to better protect the country’s “cyberspace.” Furthermore, the leakages from various political organizations during the electoral process highlighted the weaknesses of the society against cyber threats.

U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, such as financial services, transportation systems, and energy, will inevitably have a role to play.

The cyber community is now eager to see the new government’s cybersecurity plan. In addition to federal agencies, private institutions that are heavily involved in U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, such as financial services, transportation systems, and energy, will inevitably have a role to play.

Significant efforts have been made to increase cybersecurity in the U.S. and abroad. A common trend is to improve protection of what is generally called critical infrastructure. To that end, the previous U.S. administration launched several governmental initiatives, including the development of the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity by NIST (“NIST Cybersecurity Framework”). The framework is used worldwide aside major standards and is now being updated. In 2016, the Cybersecurity National Action Plan (CNAP), planned to increase the country’s Federal budget for cybersecurity to $19 billion in 2017. In Europe, the Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems (“NIS Directive”) requires Member States to adopt and publish sufficient laws and regulations to protect essential services. This is a global trend which is already visible in many countries such as France with the LPM law and China through the recently enacted Cybersecurity Law. Even international organizations such as NATO are promoting critical infrastructure cybersecurity protection.

Will President Trump focus the country’s cybersecurity program on critical infrastructure?

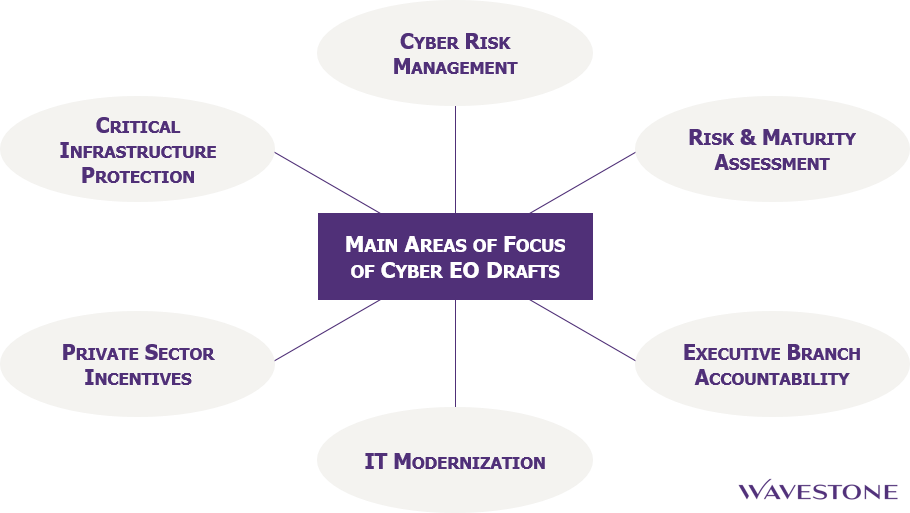

The two draft Executive Orders released show the new administration is seriously considering the issue.

The first draft Executive Order Strengthening U.S. Cyber Security and Capabilities suggests President Trump will order an extensive review of the country’s weaknesses, strengths, and enemies within an aggressive timeline. The previous administration initiated similar effort less than a month after taking office in 2009, resulting in the rather theoretical Cyberspace Policy Review.

This draft focuses on the following initiatives:

- Vulnerabilities – Review most critical cyber vulnerabilities and submit a list of initial recommendations for enhanced protection of national security systems and most critical infrastructure;

- Adversaries – Review principal cyber adversaries and submit a first report on their identities, capabilities, and vulnerabilities;

- Capabilities – Review relevant cyber capabilities and identify an initial set needing improvements to adequately protect critical infrastructure; review efforts to educate and train the cyber workforce and make recommendations for the future;

- Incentives – Propose options to incentivize private sector adoption of effective cybersecurity measures and submit recommendations.

Leveraging incentives reduces the immediate need for additional regulation or legislation.

While the review of vulnerabilities, adversaries, and capabilities is consistent with actions taken by foreign governments, a more original approach may be taken to ensure adoption of cybersecurity measures by the private sector. Indeed, the focus on Leveraging incentives reduces the immediate need for additional regulation or legislation, which echoes well President Trump’s “Two-for-One” Regulation Executive Order. On the contrary, in Europe, the NIS Directive calls for “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive penalties” to ensure requirements are fulfilled.

Based on currently available information, it is difficult to discern how and to what extent the government would be able to fully execute these initiatives, as they are relatively sweeping in scope. However, the assessment of tangible vulnerabilities and adversaries may indicate a willingness to focus on launching concrete actions.

The second draft Executive Order Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure is similarly ambitious, ordering the government to produce no less than 11 reports and requiring the involvement of the whole executive branch of the Federal Government and critical infrastructure actors.

This draft retains the initiatives on vulnerabilities and capabilities from the first draft, but the scopes are quite different. It suggests more stringent effort will be made on the protection of executive branch and less on critical infrastructure. Among other things, the government here aims to:

- Hold heads of executive departments and agencies accountable for managing cyber risk. This follows a trend already adopted by regulators in the financial services sector, for example through the NYS-DFS 23 NYCRR 500 Cybersecurity Requirements for Financial Services Companies and the NFA Interpretive Notice on Information Systems Security Programs (ISSP). Bringing accountability to the senior management level is a necessary step toward reinforced focus on cybersecurity and inclusion at the enterprise level, beyond technology departments;

- Generalize the use of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. While the framework was originally intended for critical infrastructure, it is easy to imagine it applied to federal agencies. It would likely complement and structure the usage of other materials such as the NIST FIPS PUB 200 Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems and the NIST SP 800-53 Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, which agencies are already required to leverage under the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA). It would also increase alignment of practices between the public and private sectors;

- Review executive departments’ and agencies’ risk management practices and actual risk decisions, assess whether they are appropriate and sufficient, as well as develop a plan for improvement. Such effort is consistent with the first draft but this time applies only to the executive branch;

- Develop a plan to modernize IT architecture by transitioning to shared IT services and consolidating network architecture, especially for National Security Systems. Shared IT services allow for increased security through industrialization, and consolidated network architectures are easier to protect and monitor.

- Identify authorities and capabilities to support cybersecurity efforts of entities managing critical infrastructure at greatest risk in case of cyber attack, in collaboration with those entities. The notion of critical infrastructure at greatest risk originates from President Obama’s Executive Order 13636 Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity;

- Assess the Federal policies and practices efficiency to promote market transparency of cyber risk management. No more incentives here, but a market-driven approach to foster extended cybersecurity measures among the private sector, and no reference to any new regulation;

- Identify and promote initiatives to improve resiliency of core telecommunications infrastructure. Those initiatives, likely at the Internet service provider level, would mainly focus on preventing continuously increasing distributed attacks.

The initiatives described in the two drafts are aligned with general market practices and are headed in the right direction.

Overall, the initiatives described in the two drafts are aligned with general market practices and are headed in the right direction. However, some uncertainty remains on a number of topics such as privacy and protection of PII, and private-public collaboration. Moreover, as American technology companies that have historically stored their data in the U.S. are opening more and more data centers abroad to meet local regulatory requirements, the U.S. will have to define their own data localization requirements.

The challenge for the new administration is to develop unified data protection policies to drive consistent regulations

The U.S. has led the effort in defining modern cybersecurity tools such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and the FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool but now needs to focus on execution. The challenge for the new administration is to develop unified data protection policies to drive consistent regulations, and move from a theoretical approach to concrete results.

If we are to expect actual results, the effort should enable a country-wide response that is transversal and coordinated, with sufficient oversight. Putting in charge a single agency, as announced by White House officials moments before the President’s signature was called off, may well be a first step in that direction. The new administration will have to define clear roles and responsibilities between the public and private sectors, a governance for collaboration, and a strategy to drive implementation.

Beyond this transformation, the upcoming challenge will be on the collaboration with other countries to align with foreign initiatives with a NATO-like approach, with the objective to drive harmonization of standards and requirements for a more efficient approach to cybersecurity. Stakes and expectations are higher than ever.